Review by Frank Plowright

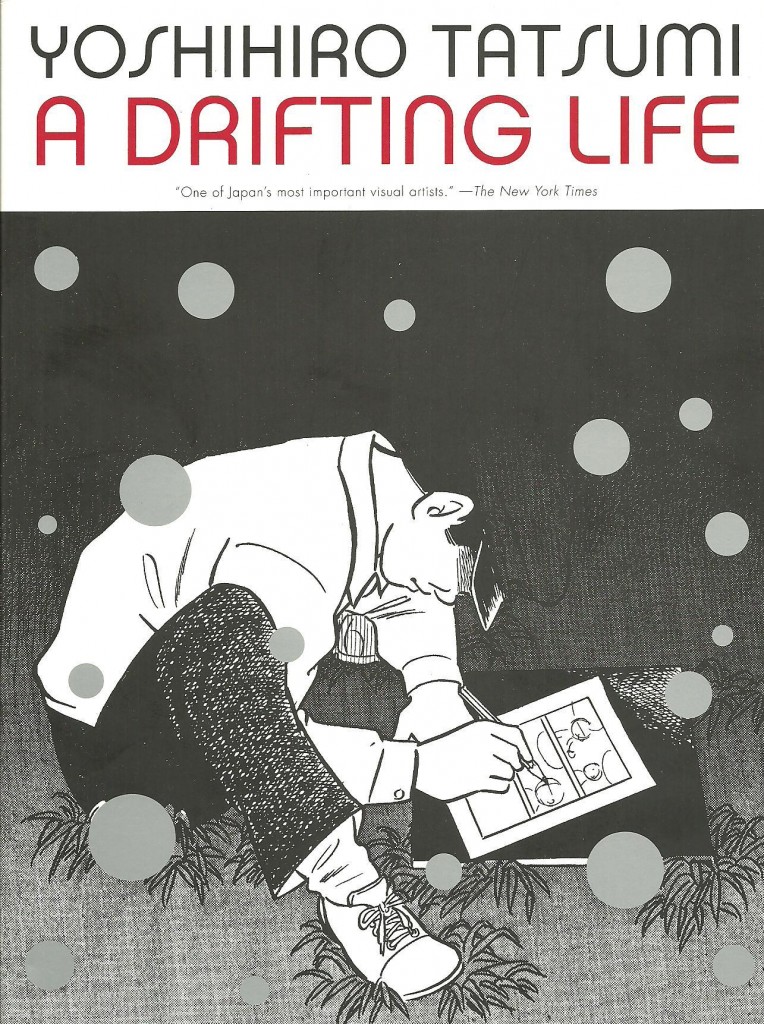

It took Yoshihiro Tatsumi about a dozen years from 1995 to complete his immense autobiographical recollections, and A Drifting Life has since won major awards in Japan, USA and France. It further inspired an animation that combined biographical elements with adaptation of Tatsumi’s earlier short stories.

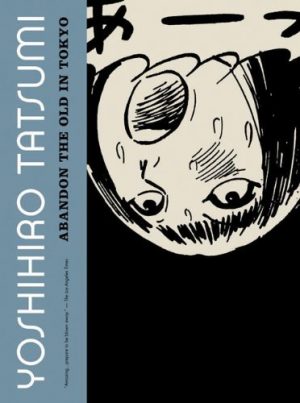

From the late 1950s he pioneered a form of graphic realism in Japan, christened gegika. Rather than creating extended narratives or returning to the same characters, his stories were brief glimpses into tormented lives. Three volumes of this work have been published in English by Drawn & Quarterly, beginning with The Push Man and Other Stories. They explored the murky areas of human experience; tragic obsessions, unfulfilled dreams and emotional crime. Reading A Drifting Life it’s not unreasonable to ask how much of this was inspired by his father’s dissolute lifestyle.

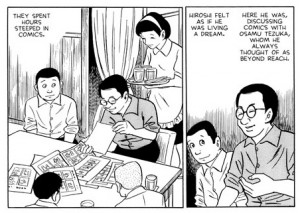

Tatsumi’s route out of the family hardship was artistic talent. Hiroshi Katsumi, his avatar here, devours manga and is presented as every bit as geeky as present-day fans when discussing their favourite creators. The sweat shops in which he began his working career were packed with artists for days at a time, cranking out work to meet unreasonable deadlines. Conditions appal, yet fired his passion and imagination. Running in parallel to his own development Tatsumi chronicles the development of manga. The only graphic novel with a similar premise that comes to mind is Will Eisner’s The Dreamer, but while brief and entertaining, it’s a country mile away from Tatsumi’s achievement.

Once established as an artist Tatsumi’s memoir is almost entirely devoid of personal reference beyond his work, as if his entire life occurs through his assorted characters, a conceit that in effect transforms him into one of them. There is a brief obsession with the woman who runs the café beneath his studio, but that’s rapidly discarded as distraction, and the emotional detachment is restored. His older brother, also later a comic creator, is a constant source of advice and criticism, and once Tatsumi approaches professional standards he’s greatly encouraged by Osamu Tezuka, whose funeral closes the book.

Tatsumi’s characters are simply and expressively drawn, sometimes occupying detail-rich background, and entirely in keeping with his philosophy of avoiding exaggeration. He returns several times to the difficulty of creating material that matches his ambition, a frequent frustration of the great artist in any discipline. Only Tatsumi himself knew whether he finally achieved this with A Drifting Life, the longer work he yearned to create.

This is an incredibly rich book, laden, but never over-burdened, with detail, constantly referencing milestones of manga and social history, and an intimate glimpse into the creative processes of a master.