Review by Frank Plowright

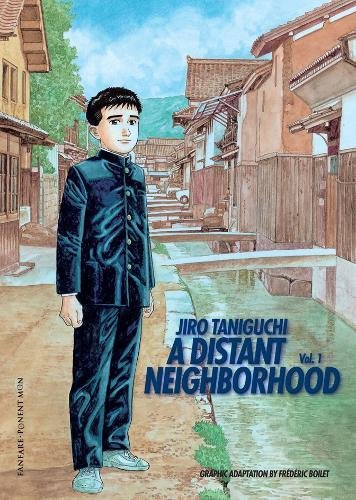

Businessman Hitoshi Nakahara is now 48, too often away from home and his family, and not giving due consideration to his alcohol intake. Returning to Tokyo drunk after another business trip, he experiences a moment of confusion and takes the wrong train, finding himself on the express service to his home town. With several hours to kill before the return service, he visits his mother’s grave, where he experiences a moment of disorientation. When everything settles his 48 year old mind occupies his 14 year old body in 1963, a few months before his father suddenly disappeared.

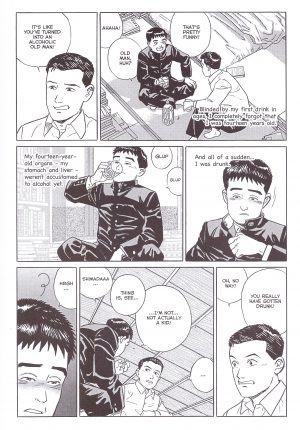

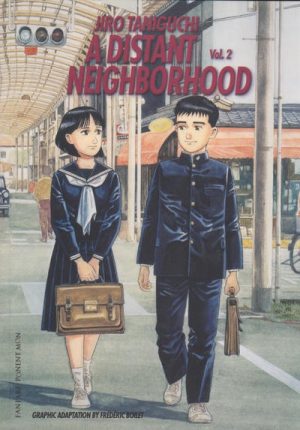

Although Jiro Taniguchi uses a form of plot familiar from cheery movies, he steers well clear of the redemptive comedy Hollywood would produce from such material. Retaining his knowledge means it’s remarked on how much more diligent Hitoshi is at school, while he can’t entirely suppress long learned habits like drinking. Given the opportunity to impress the girl every boy in his class fancied, he takes it. Because Taniguchi draws the fourteen year old Hitoshi so sympathetically, it’s a while before realisation dawns that what seems natural and innocent is actually anything but on Hitoshi’s part, yet it’s disturbingly left lacking comment. Thankfully, this is addressed, very effectively, in volume two.

Of the two parts this is the simpler, Hitoshi raising questions he never gets to grips with, enjoying the company of people he’d long forgotten, with a nice touch being his noticing the suppleness of his own younger body and the greater movement it permits. Taniguchi’s precise simplicity brings this to beautiful life, expressions conveying thoughts the dialogue doesn’t. His locations are similarly pastoral and calm, elegant throughout.

Some aspects of Japanese culture, possibly changed since 1963, will seem strange to Western readers, one example being a teacher lecturing Hitoshi on discovering him eating at a restaurant unaccompanied by an adult. None of these moments, however, affect the greater understanding. While drama takes precedence, Taniguchi supplies an occasional comic moment, such as Hitoshi’s fondness for alcohol having a different effect on his younger body, but A Distant Neighborhood is generally a quiet reflection on the importance of family and belonging. It ends just as Hitochi begins getting to grips with the bigger question of what is likely to prompt his father’s disappearing a few months down the line via a heart to heart with his grandmother. The conversation continues in volume two, but more conveniently, both are combined in a 2016 hardcover.

A Distant Neighborhood won the Excellence Prize at the 1999 Japanese Media Arts Festival.