Review by Frank Plowright

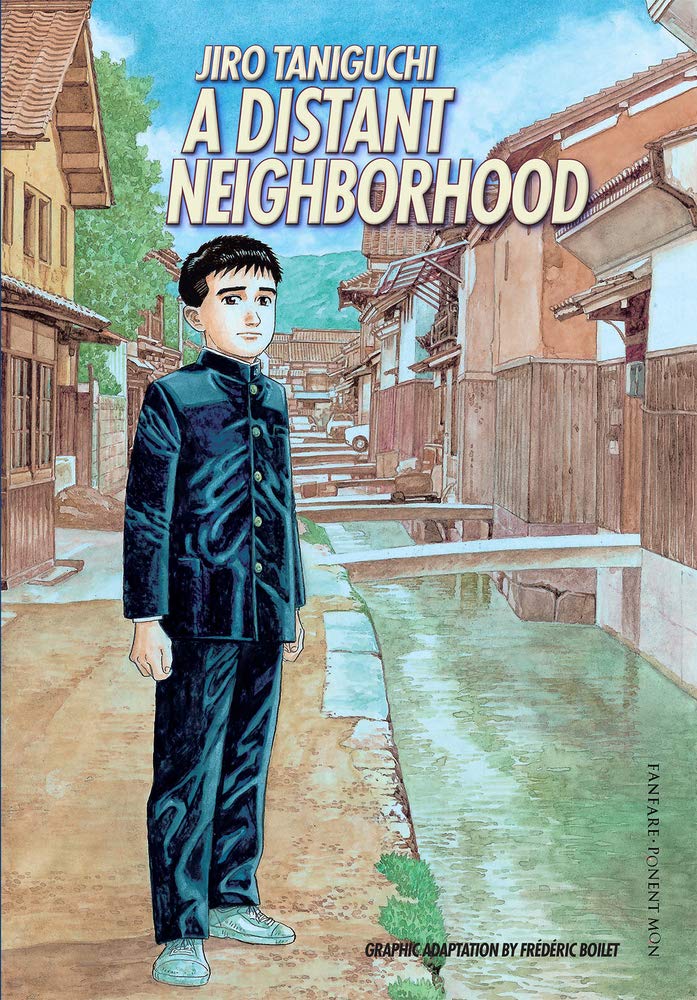

Hitoshi Nakahara has a moment of confusion when returning home from a business trip and takes the wrong train, boarding the express service taking him back to the town where he grew up. On the journey he realises he’s the same age as his mother when she died, and there are similarities between their characters, both too focussed on one aspect of their lives to the neglect of others. Can he change?

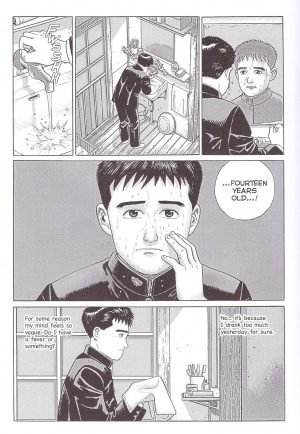

That question is asked in unusual circumstances, as Hitoshi falls asleep at his mother’s grave and awakens with his mind occupying his fourteen year old body 34 years in the past. In 1963 his family is still together, his father’s not disappeared and even his grandmother is alive. Similar scenarios have been played for laughs in Hollywood movies, but Jiro Taniguchi doesn’t take that route beyond Hitoshi considering it wise to keep his true status a secret. He investigates how a grown man in a teenager’s body copes with school, how knowing the future can be a curse, and supplies an introspective consideration of how much a revised youth will affect his future.

As with all Taniguchi projects, the fully realised artwork is incredibly precise, each panel drawn very simply, yet a work of individual beauty and refinement. It accompanies a leisurely rolling out of infinite possibilities. Hitoshi’s adult mind picks up on elements he’d not noticed during childhood, how the personalities of friends led to what they’d become, and the little moments between his parents, with his father’s imminent disappearance hanging over everything. Can he solve that mystery?

Understanding human emotion is key to A Distant Neighborhood’s appeal. Not everyone behaves as they should. Because Hitoshi looks fourteen, a date with the girl everyone loved in his high school days seems natural and innocent, the reader having to stop to consider how sordidly opportunistic it is under the circumstances. It seems a matter Taniguchi’s going to bypass without comment, but it’s addressed in a brilliantly unconventional way, first via contrast, then by a realisation, and what’s really impressive is how that ties into Hitoshi’s father’s situation.

Any form of time travel opens infinite possibilities that are simultaneously constricted. However, because A Distant Neighborhood is drama, not science fiction, it largely avoids considering the time traveller killing a butterfly and returning to their present to discover everyone speaking Albanian. Instead Taniguchi concentrates on the feelings and possibilities. He’s always contemplative, highlighting the quiet moments, and the result here is a touching meditation, where almost every character has a surprise to drop at some stage as Taniguchi plays readers superbly. It’s a master at work.

This new hardcover edition is a welcome replacement for the previous splitting of the story over two volumes, which earned Eisner Award nominations, and prompted Sam Gabarski’s 2010 film. That takes a slightly different approach, clarifying matters of honour left unspoken here as automatically understood by a Japanese audience, and recasts Hitoshi as a disenchanted French comic artist. Just in case it puzzles, the credit for “graphic adaptation” given to Frédéric Boilet is for adjustments to the art required due to the process of presenting A Distant Neighborhood in European format reading from front to back rather than the back to front Japanese process.