Review by Ian Keogh

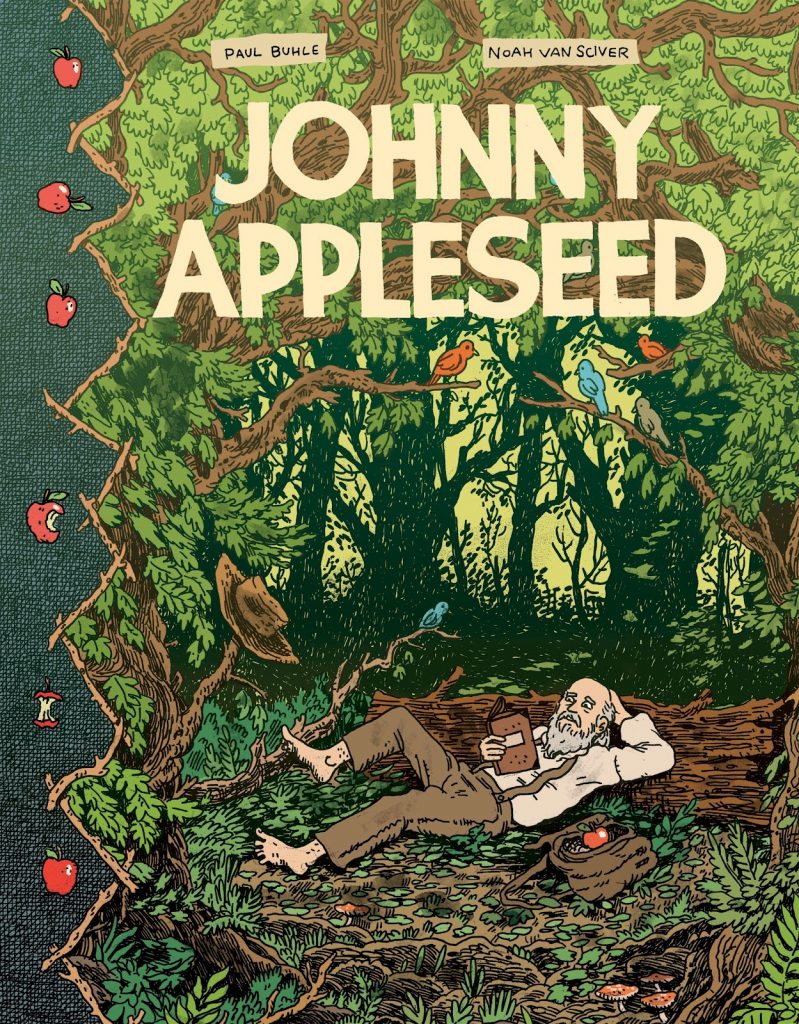

Johnny Appleseed is name that will have seeped into the consciousness of many North Americans without their necessarily knowing it was a nickname for a real person. John Chapman was a compulsive wanderer who scattered seeds during his travels over the first half of the 19th century, and most of what is known about him comes from journalistic writings decades after his death, when he’d begun to be romanticised. Not, then, perhaps the most promising subject for a biography.

Paul Buhle and Noah Van Sciver circumvent that by wandering through Chapman’s biography in the same random way he wandered the Eastern states, with plenty of stops and diversions along the way. They look into the spread of apples, pioneering naturalist John Muir, calls for women’s rights, and Socialist co-operatives, and explain the times and surroundings when a United States existed in name, but occupied only a third of the current territory when Chapman was born. Midway through his life the Louisiana Purchase almost doubled the size, extending the country as far West as Montana, while the occupation was founded on a remorseless lack of concern for Native Americans. Numerous eccentric religious faiths manifested from 1750, and from meeting many of them Chapman devised his own personal beliefs, although largely from adapting the doctrine of Emanuel Swedenborg, one of the more out there preachers, who’s quoted several times. Buhle acknowledges contrary beliefs about Chapman, especially modern interpretations of his religious views.

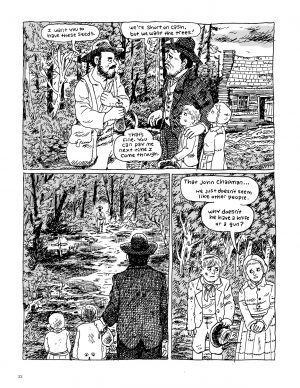

Chapman’s simple life is simply drawn by Van Sciver. His illustrations are two-dimensional and lack elegance, but also detailed and first rate in conveying rustic people who had few comforts. His posed agitators and preachers have a great energy, and he fully fills backgrounds, but without distracting from what’s important.

At times Buhle becomes carried away with Chapman’s influence, stretching a point a little too far, such as a strained connection with Abraham Lincoln, but Buhle’s thoughts and extrapolations are always interesting. Toward the end he connects Chapman with other notable wanderers, economic migrants and the rail-riding culture, and considers his influence, often pure chance.

A brief coda looks at others who’ve lived with nature and become figures of inspiration, such as Saint Francis and Robin Hood. That’s followed by Buhle’s three page essay about Johnny Appleseed, and Van Sciver’s sobering and sad acknowledgement to BYU for providing enough money to allow him to avoid working in a bagel shop and to finish the book. Anyone who enjoys a meander through the past will find Buhle and Van Sciver enthusiastic hosts, occasional clunky dialogue notwithstanding. At the very least prepare to be astounded by their revelations. These days exchanging land for seeds is almost beyond belief.