Review by Graham Johnstone

Oliviér Schrauwen dazzled with his graphic novel debut, Arsène Schrauwen, a poetic exploration of his uncle’s memories of the Belgian Congo. Oliviér’s early shorts impressed at the time, and gain additional interest as a prelude to the later book.

Those stories mostly appeared in the Fantagraphics anthology Mome, exemplifying an editorial shift from literary, to visually driven, comics. The publisher subsequently gathered Schrauwen’s contributions as The Man Who Grew His Beard. It’s a diverse collection, united only by a bearded protagonist. Actually, he’s less a ‘protagonist’, than a simply man looking around, reacting to the situations the author sets before him.

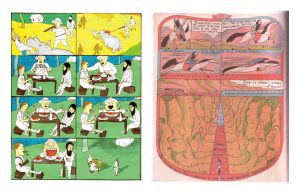

The most obvious precursor to Arsène Schrauwen, is the current volume’s opener ‘Congo Chromo’. The Belgian Congo, was a particularly brutal example of European colonialism, something contemporary Belgians like Schrauwen are willing to confront. It opens with the bearded man contemplating the world, and reluctant to engage with the jovial colonist beside him. It’s entirely wordless, but Schrauwen conveys the characters’ reactions through dramatisation, notably by the literal walking away from a hippo steak, offered by the man who just shot it (pictured, left). The three men here represent different approaches to this colonial situation: the ruthless pioneer whose bonhomie overcompensates for the brutality; the hapless victim; and the bemused observer. The burlesque humour counterpoints the brutality of the story by acting as a distancing device. Schrauwen offers no retribution or moral lesson, instead leaving the reader to have their own reaction to this vivid and visceral experience.

‘The Imaginist’ also has a sociological dimension, with this bearded man’s physical circumstances anchoring his flights of opulent imagination. ‘Outside/Inside’ plays mischievously with fictional perspective and structure, shifting from observed to imagined versions of situations. Nuns changing a tyre become a coach of aspiring harem wives, now rescued by the bearded man, for foreseeable reward. ‘Hair Styles’ riffs on the archaic pseudo-science of physiognomy, absurdly inferring character from hair types like ‘docile’, ‘rigid’ and ‘frivolous’. The stories are sometimes less narrative than musical: melodic and rhythmic reiterations of motifs, like the final page of ‘Hair Styles’, with its six men (or versions of one man) with different hairstyles, gazing at his drawings of corresponding women. Entertaining as these scenarios are, their strength is as springboards for sequential artistry.

Schrauwen is an inventive visual thinker, and a restless, versatile artist. His charmingly naive depictions may be rendered in weathered lines and sepia tones, or lurid off-kilter palettes. ‘Outside/Inside’ starts in documentary monochrome. The transition to the subjective ‘inside’ is signalled by a Wizard of Oz style introduction of colour, and presentation as iconic ‘stained glass’ panels (pictured right). This tailoring of the art style for each story and strand, adds visual appeal to the whole.

These comics are best summed up by artist/teacher Paul Klee’s, idea of ‘taking a line for a walk’. Schrauwen seems to take an idea and similarly wander through the panels, each suggesting the next. Happily, he has the visual imagination, wit, and story nous to reach a welcoming destination. Every page here is an inventive, visual treat.

The Man Who Grew His Beard, highlights the disparate strands Scrauwen would weave together so convincingly in the sustained narrative of Arsène Schrauwen. The colonial themes foregrounded in ‘Congo Chromo’ also surface in ‘Outside/Inside’. The remainder introduce Schrauwen’s mischievous methodologies of detached presentation, enthralling subjectivity, visual imagination, wit, and cheeky humour. His irreverent approach to literary and artistic traditions may make him a niche figure, but he’s an wonderfully engaging host of that niche.