Review by Frank Plowright

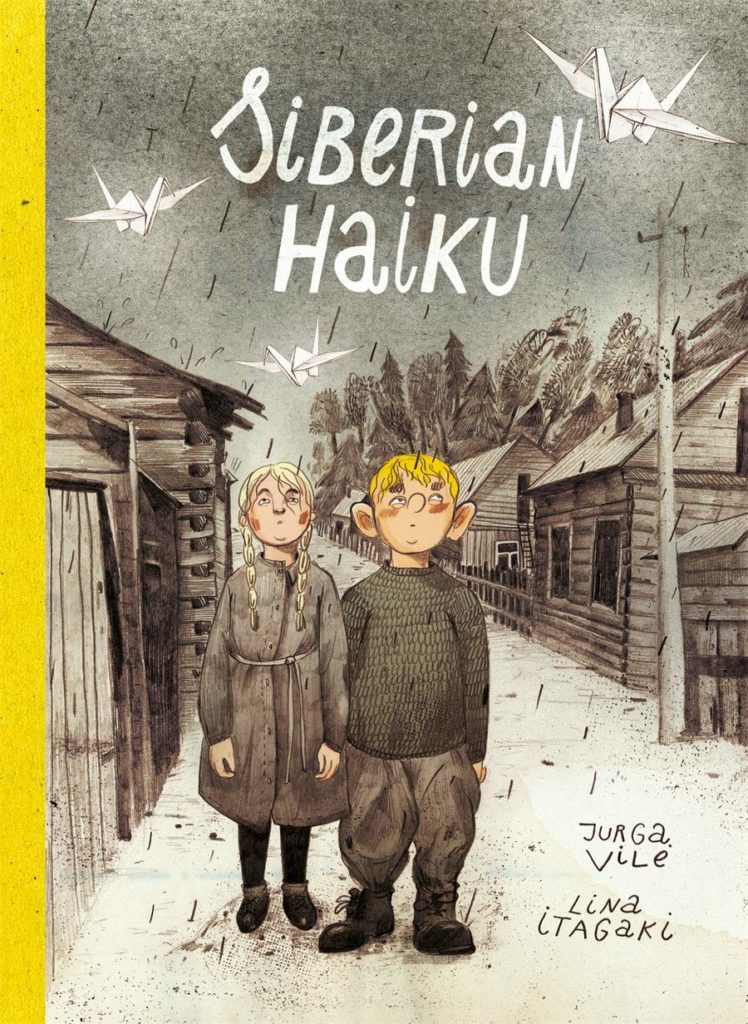

Such are the multiple atrocities of World War II, so many remain little known beyond the families of those directly affected. When the Russian forces pushed the Germans back, the yoke of oppression was merely transferred in many countries, Lithuania among them. In a country that had only achieved independence just over twenty years before, the desire of the citizens not to be incorporated into the Soviet Union was considered subversive. The Soviet response was to ship many Lithuanians to frozen Siberia, thousands of miles away. As a child, Jurga Vilė’s father Algis was among them, and Siberian Haiku is presented as if his childhood narrative.

It’s the killing of his pet goose that really brings home to Algis that being rounded up in the middle of the night and being placed in livestock train carriages isn’t a big adventure. Men are separated from their families and not seen again, and everyone who survives the subsequent journey ends up in a filthy Siberian barracks hut. While there are guards, the children fend for themselves while the women work.

Vilė uses Algis’ voice as a child, explaining nothing in adult terms, and Lina Itagaki follows that lead. Deliberately flat and childlike art gives the events a greater resonance than graphic realism, being a constant reminder that a child is living through and witnessing atrocities, and so rendering them even more tragic. People are generally drawn as cheerful, as we learn early to avoid the Glum Bunch, and some scenes require a greater complexity than a child could draw, with Itagaki’s illustrations then resembling the art from children’s books. Itagaki also designed the distinctive font used for the lettering, employing it for the English translation as well as the original version.

It’s perhaps condescending to point out moments of brightness in appalling circumstances, but they exist. The one book Algis’ Aunt Petronella manages to smuggle with her contains haikus in Japanese, a language she couldn’t read from a country she’s obsessed by, yet it’s later responsible for a moment of unusual warmth. So is the formation of a choir, an attempt to lift spirits, and Petronella’s obsession with Japan again produces uplifting art via origami cranes seen on the cover. Diagrams are considerately provided for readers to make their own. A notebook feel is cultivated as comic sections mix with blocks of handwritten text accompanied by illustrations, the scrapbook feel extended by incorporating recipes, introductory portraits accompanying biographies of all prominent Lithuanians seen in Siberian Haiku, and Algis’ imaginary letters to his Uncle. More tragic letters also feature, these from other forced emigrants.

There’s almost a curse about Algis’ young life. That his daughter writes Siberian Haiku would indicate his survival even if that weren’t shown in the opening pages, but another ghastly event is perpetually just a few pages away. However, despite the promotion of constant dread, not everyone’s story ends badly. It’s a comfort to keep in mind.

A wrap-up is rapid, and a final paragraph updating raises more questions than it answers, Vilė seemingly restricting what she discloses. Lithuania’s second spell as a free nation has currently outlived the first by a decade, or half as much again. Did Algis live long enough to experience freedom for the first time since infancy? What kind of man did he become? Perhaps the thought was that his story should end with a return home. Stories of persecution and repression shouldn’t be comfortable reading, and even if a generation removed, this memoir brings that home. It’s horrific, fascinating and drenched in compassion, so well worth your time.