Review by Frank Plowright

Marzi was quite the departure for Vertigo, being their first translation of foreign material and one of their few explicitly autobiographical graphic novels.

Autobiographical comics flourished in the 1990s, but sunk under the weight of navel-gazers believing their day to day existence was primed to engage others. Graphic memoirs published in the new millennium largely avoid this pitfall, being produced either by people who have a unique perspective and something to say, or those offering insight into experiences new to most readers. The best combine both, and Marzi drops squarely into that box.

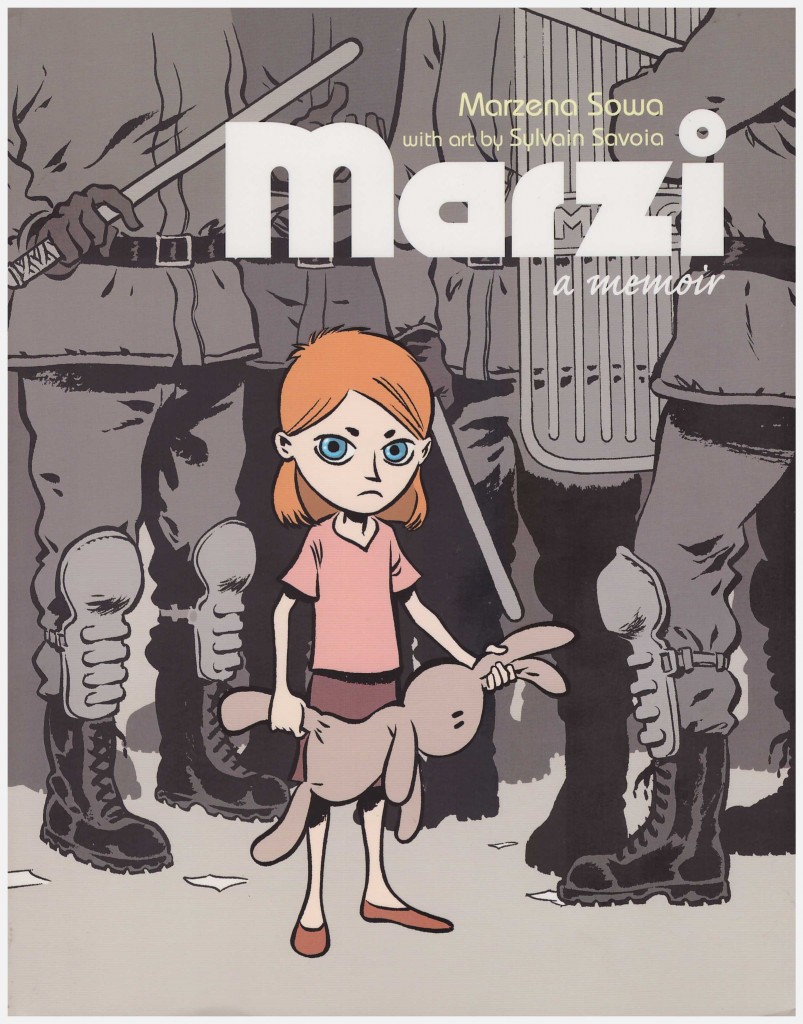

Those raising the subject of whether a graphic novel can truly be autobiographical if it’s drawn by someone not supplying the narrative voice should take a look at Harvey Pekar‘s intensely personal work. Marzena Sowa might not be illustrating her childhood, but it’s her experiences and storytelling that render Marzi unique. Accomplished artist Sylvain Savoia is very much an extension of her brain here.

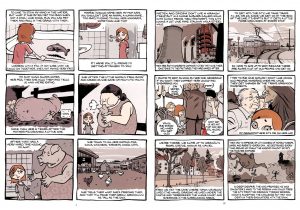

Savoia tailors his art as if presenting a succession of snapshots, occasionally basing illustrations on actual photographs. His wide-eyed Marzi deliberately exaggerates the young girl pictured in the rear of the book for purposes of empathy, although she’s far more expressive than the static and unsmiling child in those pictures. The cartooning is always convincing and well-considered.

Marzi covers the bulk of what was published over six volumes in France, then two heftier collections, and the subtitle of the first, translated as Poland through the Eyes of a Child, conveys the theme. Sowa spent her childhood behind the iron curtain in Communist run Poland, the title being the diminutive of her name. She has both an astounding memory, and an admirably convincing manner of evoking the ways of children to whom the world doesn’t always quite make sense. That’s helped via a formidable naturalistic translation from Anjali Singh, whose credit really shouldn’t require searching out.

Marzi’s childhood encompassed tumultuous times in Poland, with the Communist leader Jaruzelski struggling to placate the workers of the country as the Solidarity union increasingly challenged his dictatorial authority. This is personalised as Marzi, in a chapter titled ’11 Days’ conveys her foreboding and how she misses her father as he participates in industrial action. That, though, is only a small part of a glorious anecdotal recollection of what to us is alien culture, yet is life as it’s lived as far as Marzi is concerned. Apart from the Latin American soap operas, strangely syndicated in Poland, to which she becomes addicted. There are many happy occasions, but also Marzi constantly having to deal with the moods of her cold and authoritarian mother, her own personal Jaruzelski, who seems ill-suited to raising children.

This is not exactly the same material as seen in the original European editions. It’s been cut down, and most dramatically instead of being coloured in the original bright shades it matches the European collected editions in using a limited palette of brown and rust, with highlights, most frequently Marzi’s hair, picked out in red and orange. It’s an effective change, presumably meant to accentuate the deprivation of the times.

Marzi is a graphic novel with widespread appeal. She comes over as a likeable and curious child, and has dozens of charming stories, without ever slipping into saccharine sentimentality. This is the mythical graphic novel you can give anyone.