Review by Frank Plowright

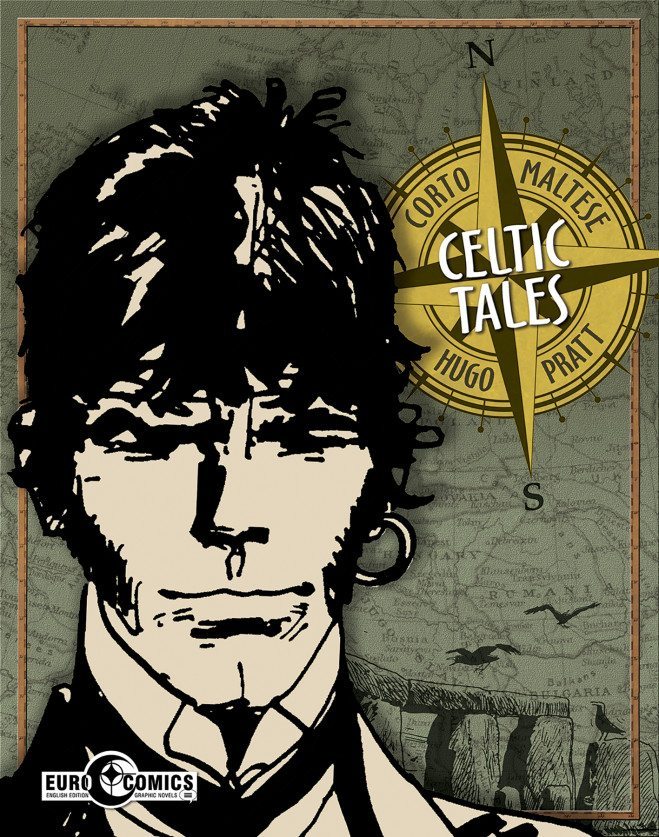

Hugo Pratt created his Corto Maltese stories in the 1960s and 1970s. They’re revered around the world well beyond even the current audience for graphic novels, yet even with the advances in creative intellect applied to the medium they’re still unique. The reason may simply be that true genius cannot be effectively copied. If a single volume has to be distilled from an impressive dozen as the essence of Corto Maltese it’s surely Celtic Tales. Over six stories it doesn’t just chronicle Corto’s 1917-1918 tour of Europe, but Pratt’s dazzling virtuosity and mastery of the story form. Corto Maltese the adventurer is common to almost all the books, but Celtic Tales also features mystical interludes, historical tragedy, puppetry, and the concept of Britain’s mythical creatures threatened by possible German invasion and their accompanying Teutonic legends. Opening in Venice, where he’d return in Fable of Venice, it closes with Corto among the Australian troops fighting the battle of the Somme. Thinly disguised versions of real people have cameos, such as a future Greek shipping magnate and an American writer, while others such as the Red Baron are named.

The national rivalries of World War I float over Corto, who is always his own man, but Pratt initially uses the conflicts around Europe to spur Corto’s searches for hidden gold. It’s clarified that to him this is the means to adventure, not an end in itself, and he cares little for the reward other than how it can help others, which actually makes him sound more considerate than he often is. It’s also a rare insight into a largely unknowable person. What we know of Corto is generally via the love, trust and affection others have for him, and their disclosures in passing, a stay in a Perth jail referenced, suggesting he was also in Australia at one point. However, Pratt prefers to maintain mystique, so deliberately chose a place name also found in Scotland. He additionally offers an occasional gnomic mythologising pronunciation from Corto, one here being that he’s not decided when he’s going to die. His presence anywhere is largely prompt rather than protagonist, and that’s well represented, especially when he organises an effective rescue of stolen gold without appearing in person until the final five pages.

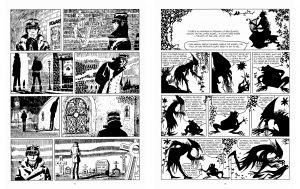

Pratt’s chosen artistic form is impressionism, but his lines and splodges of ink combine to cement visually memorable locations. Smoky Shakespearean half-worlds, Irish cemeteries, Somme battlefields and the eccentricity of Stonehenge are all vividly recreated, the personalities are richly presented and easily distinguished, and a shadow puppet show is brought to beautiful life in delicate silhouette. This is unusually obvious showmanship on Pratt’s part, as he’s more generally inclined to conceal his talent, the stories flowing so well it passes unnoticed, but the display fits the theatrical emphasis of several pieces.

The tragic Irish story mulls on heroism and myth, but otherwise a quirkiness infuses the content, never more so than in the penultimate tale. It features an arch Red Baron, literary criticism, pontification on wine, an impossible shot and a glimpse into the future. It’s great.

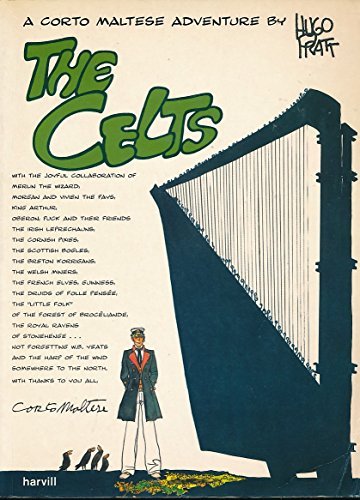

Everything that makes Corto Maltese such a beguiling series is present in quantity over these pages. The moods shift, the art is wonderful, and there’s considerable variety. If you’ve heard about Corto Maltese and aren’t sure what to sample, Celtic Tales is the one. It was previously available in English in 1996 as The Celts from Harvill Press, but this translation is better. Corto’s next destination is Africa in The Ethiopian.