Review by Ian Keogh

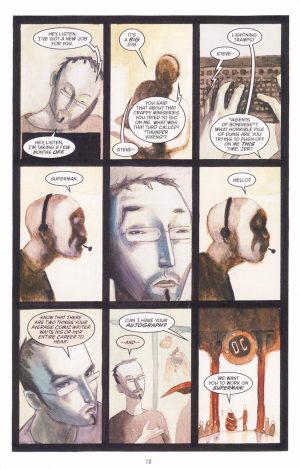

There’s a circular logic to the entrance point of It’s a Bird. Most writers of superhero comics would consider an offer to write Superman a pinnacle, their entire career being validated by writing the adventures of the most popular superhero on the planet. Steven T. Seagle isn’t most writers of superhero comics. Which is why “Steve” has been asked to write Superman. And it’s when his life starts crumbling.

He doesn’t want to write Superman, but he’s a writer, and the thought is implanted, so ideas start popping into his head, and as he goes about his day events in Steve’s own life begin to develop parallels with the Superman mythos. Not everything, but enough, and with Superman entrenched in his head he contemplates the aspects of the character he’s unable to relate to, and why.

Around a third of the way through the book another Superman writer vocalises what every reader has realised (because Seagle’s guided us there), that he’s overthinking. To Steve the character represents power and enforcement, and in too many aspects of his own life he’s lacking power. He’s concerned about the heredity of Huntingdon’s Disease, his father is missing, and his girlfriend wants to have children he feels he’s not ready for. And in the background there’s a memory that’s been repressed for years, one intimately connected with a Superman comic.

Seagle’s Superman analogy can be applied beyond the content. Writers reveal, but also conceal, and while presented as autobiographical, the back cover blurb considers It’s a Bird to be semi-autobiographical, as much Clark Kent as Superman. It’s accessible and emotional, a cry for help concealed within the behaviour of a dick.

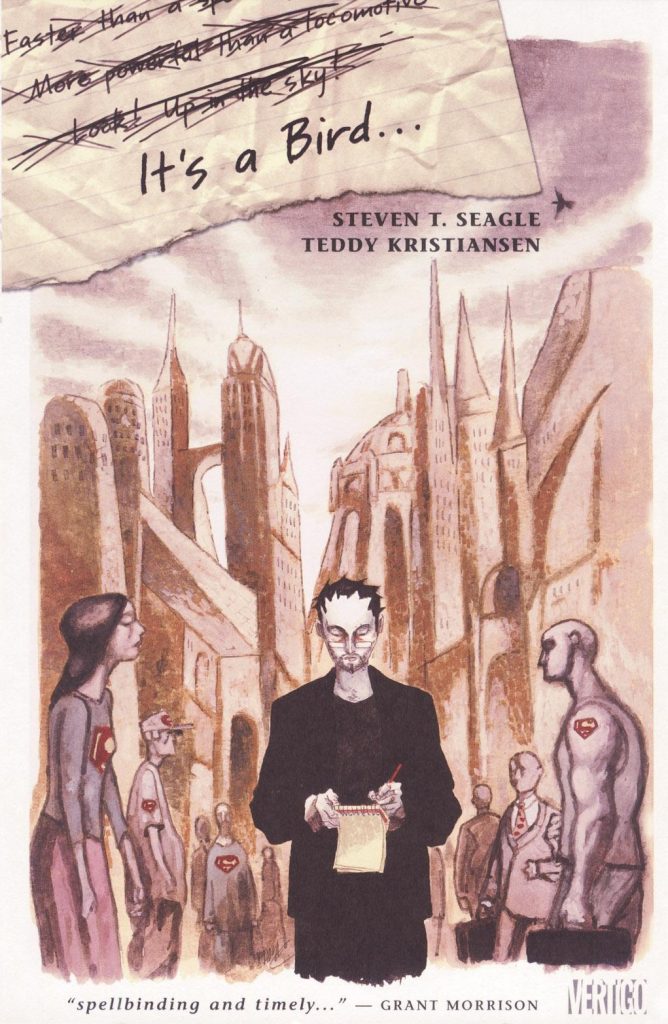

It’s a Bird is concerns the introspection of a writer, but requires an artist to reveal all. Considering the focus is almost entirely on Steve, it might be surprising to learn that Teddy Kristiansen is very much an equal partner. His choice to render most of the book in faded pastel watercolours, reflecting Steve’s worldview is both astonishingly brave and exactly right. Was it Seagle or Kristiansen who decided on the narrow lenses through which Steve views the world? They’re responsible for a sharp piece of visual allegory. The needs of the script require an adaptable artist, and while an unsettling spiky style conveys the everyday scenes, Kristiansen is a virtuoso at switching to other forms for specific purposes. He resists the temptation throughout to lapse into standard Superman depictions, and creates several thoughtful alternatives.

This isn’t an easy read, both due to the subject matter, and the subject further disintegrating on every page. Graphic novels may have progressed immensely in a relatively short time, but very few avoid a likeable character, and Steve’s not very likeable for most of the book. His rapid journey into the light at the end is the weakest element, a narrative convenience, but the remainder is compelling.

One final irony should be mentioned. Steven T. Seagle did write Superman for a while in 2003, and after this captivating monologue about why he’s not suited, his isn’t the most fondly remembered run, and as of 2018 hasn’t been issued in collected form.