Review by Frank Plowright

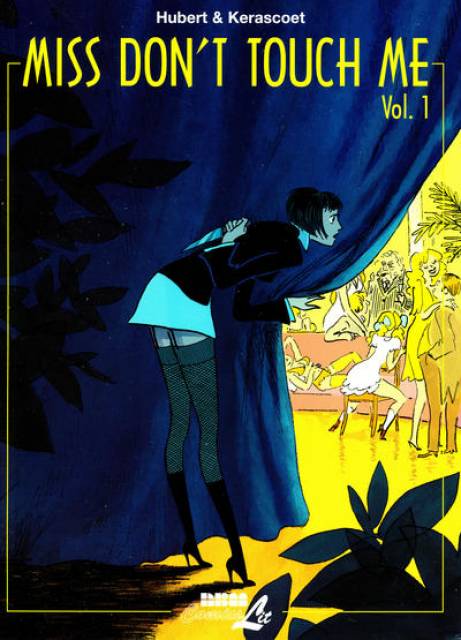

The reserved Blanche and her more outgoing sister Agatha occupy the decrepit attic room of the old building where they’re employed as servants. This is 1930s Paris, where a killer named the Butcher is active, depositing brutalised and dismembered corpses around the city. Blanche witnesses the Butcher in action through a hole in the wall, without identifying him, but it’s Agatha who pays the price, being shot as she approaches the gap several hours later. By the time Blanche has summoned help Agatha’s corpse has been re-arranged to resemble suicide, and no-one will believe what Blanche witnessed.

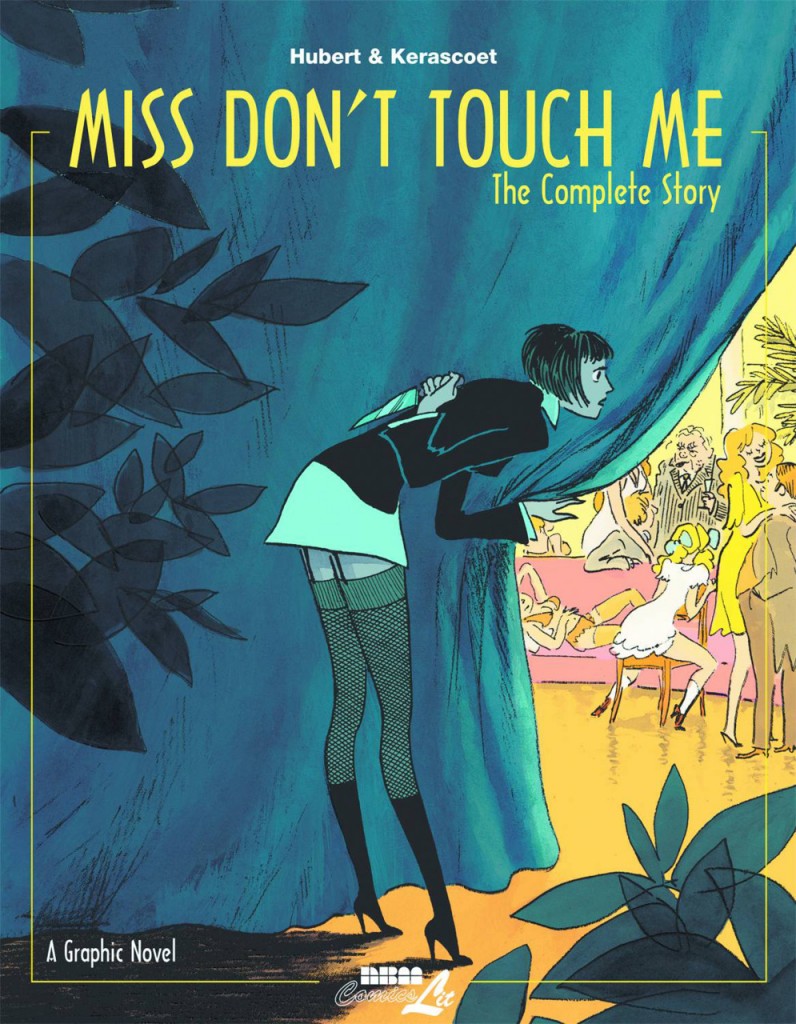

The title comes from a sarcastic term applied to women who shun advances, and Blanche is instantly appraised as such a type when she seeks employment in a brothel, but carrying out domestic duties rather than offering herself. Many of the Butcher’s victims have been prostitutes, and Blanche hopes to learn of her sister’s killer.

No, the plot doesn’t withstand logical scrutiny, but that’s irrelevant as the story opens into something charming and compelling. Blanche learns substantially more of life in a few weeks while maintaining her chastity, earning her keep as a dominatrix and working out her frustrations on clients. She does have an angel looking out for her, tempering her blundering, and by the satisfying conclusion we’ve all come to know and love Blanche.

The sting is drawn from what might otherwise be a prurient setting and brutal scenes by the beautifully expressive cartoon art. Credited to Kerascoët, that’s an alias used by the team of Sébastien Cosset and Marie Pommepuy. Their Blanche has a wide-eyed innocent allure, but none of the cast are overly sexualised.

The original French publication of this content ran to four albums, and NBM initially issued them paired. This was logical, as by the conclusion of the second French album the Butcher has been revealed and the glimpse into Blanche’s life appears to have run its course.

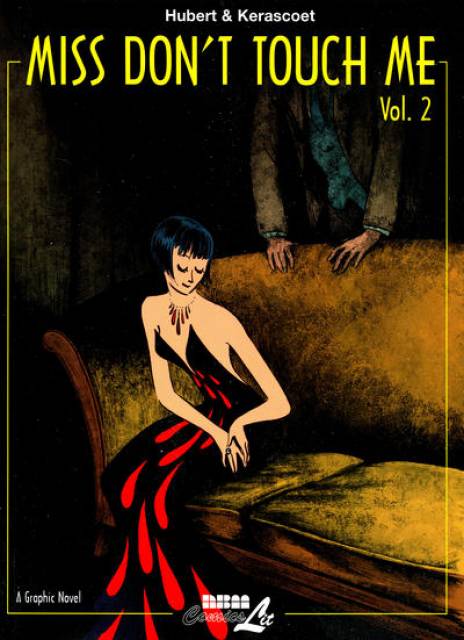

Had the book concluded after two chapters it would be five star material, but as Hubert (Boulard) continues the story it transforms from the compulsive to the impulsive, although remains stunningly drawn. Having spent the first half of the book confining Blanche’s world, the second part springs it open again. Were this unconnected to the previous chapters it would be a perfectly serviceable tale, but as a continuation it fails. Blanche had progressed from her previous ingénue characterisation, yet reverts to believing in fairy tales, all evidence to the contrary. Her mother turns up, complicating matters, and while Blanche retains her dogged tenacity it’s as if she’s another character entirely. What a shame.