Review by Ian Keogh

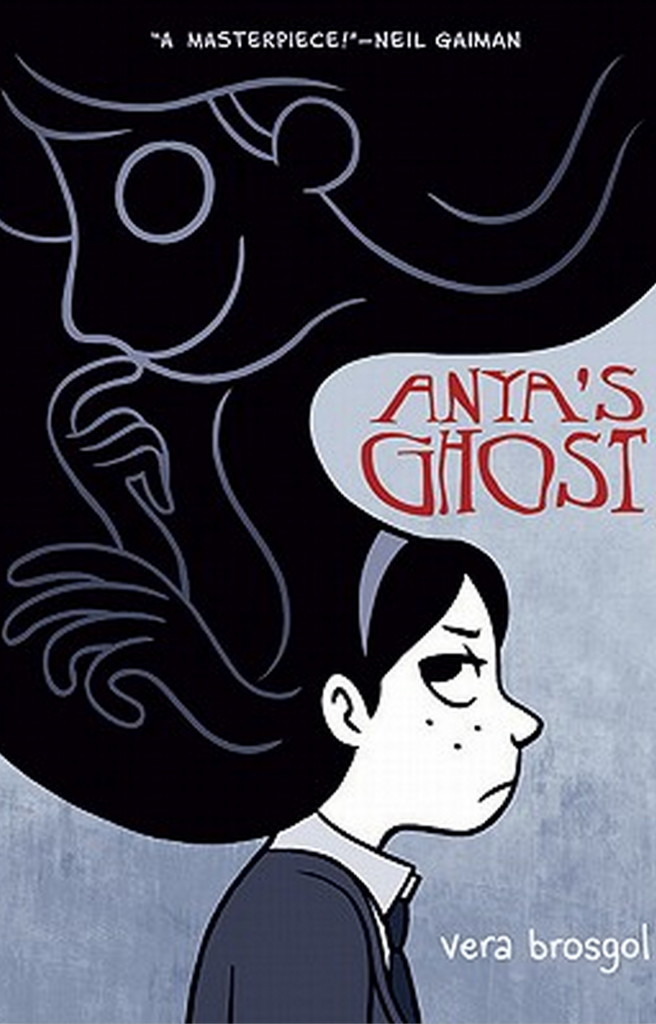

Scoring Neil Gaiman to label your first graphic novel “a masterpiece” is very much the coup, and it easy to see why he likes it. It’s the sort of spooky children’s fiction he’s explored himself with Coraline, and to an extent with the Dead Boy Detectives in Sandman, but Vera Brosgol’s work has a far lighter touch about it.

Anya is the teenage daughter of Russian immigrants to the USA, and in addition to experiencing the teenage awkwardness common to her age, she has to cope with the embarrassment of her mother not entirely fitting in to American society. Probably the last thing she needs is a life-changing event. This begins with Anya falling down an old well, the bottom of which already contains a skeleton.

That’s the remains of Emily, who fell down the hole in 1921, and now manifests as a ghost. When Anya is rescued, ingeniously, the ghost tags along, and Anya is soon ruining her social reputation further by seemingly talking to herself. Having a ghost as your pal has its upsides, though, and all of a sudden things seem to be improving for Anya. At school, anyway.

Brosgol surely feeds her own Russian heritage into events, particularly in domestic scenes of Anya’s frustration with her mother, and there’s a reality to the awkwardness of teenage years. This is not just with regard to Anya, as other lives are unravelled. Emily proves helpful, adjusting to the modern world, and after a while Anya concludes she should reciprocate, and offers to help Emily’s ghost. There’s a very clever game being played. Brosgol’s cheerful cartooning and good sense of comic timing lures us right down the garden path, and when she starts to spring her surprise you’ll still be suckered despite knowing there is one.

Without giving too much away, the mood becomes continually darker as the book progresses, although never to the point of shedding the all-ages label. It also becomes evident how well Brosgol has plotted. There’s not a character wasted here, and they’re all well defined, with the conflicted Anya charming and sympathetic.

To begin with Brosgol’s animation background is evident in her storytelling, as her pages feature too great a focus on the associated art of storyboarding. For animation every movement is laid out, and so it is here, except the beauty of graphic novels is that readers make the leaps with their mind between panels, so there’s no need to show everything. That’s only a problem at the start, and it’s really surprising how adaptable the friendly style is for events that aren’t as cheerful.

The book’s final quarter is dominated by a quest leading to some unexpected character based revelations. Once again, these have been extremely well set up. By the conclusion some lessons have been learned and we’ve all been thoroughly entertained. Yes, Gaiman’s indulging in hyperbole, but not to a great degree.