Review by Karl Verhoven

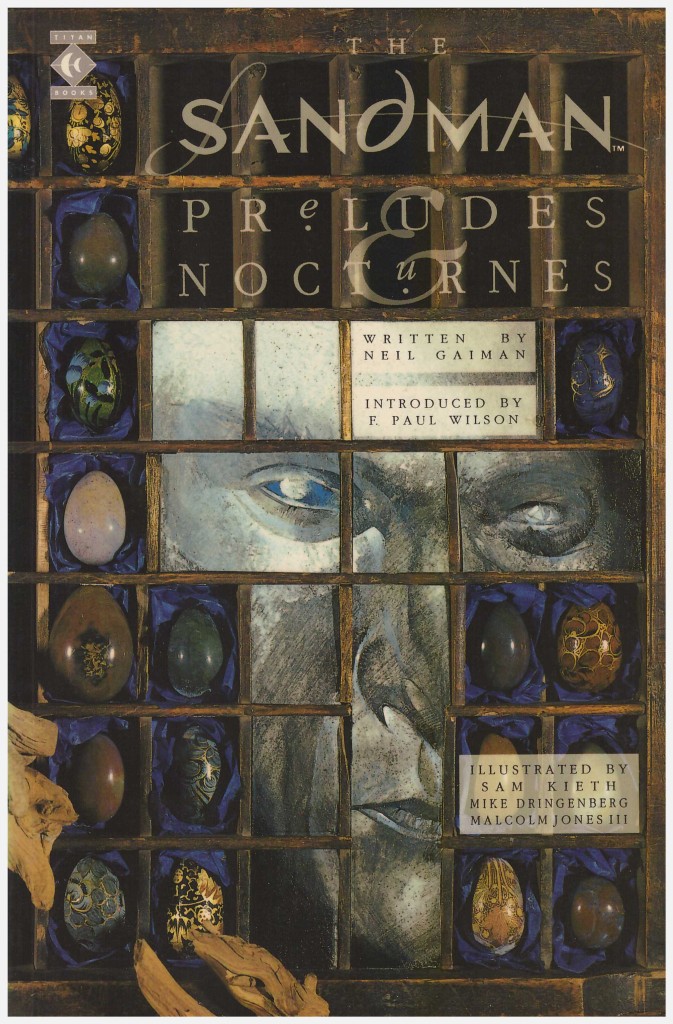

This is the collection of material that introduced Neil Gaiman’s Sandman to the comic reading public. In the light of what it became, these early episodes are very much groping in the dark, blending fantasy and horror, and nipping around the outer fringes of the DC Universe.

Sandman is an immensely powerful mystical force known as both Morpheus and Dream, and yet he’s been confined by a human magician. Roderick Burgess seeks immortality, believes he’s trapped Death, and will trade freedom for his desires. Gaiman finally revealed how this situation came to pass over 25 years later in Overture. A human lifespan is negligible for Morpheus, so he merely sits out his captivity awaiting Burgess’ inevitable demise. Once freed, he sets about recovering his accoutrements via some familiar faces.

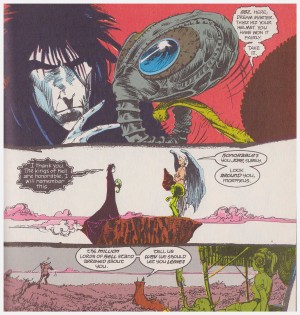

This is an awkward start to a classic series. As good as he’s been elsewhere, initial artist Sam Kieth’s reaction to Sandman is quoted in Gaiman’s afterword as “I feel like Jimi Hendrix in the Beatles.” He’s right. The visual content improves when former inker Mike Dringenberg takes over the art. Dringenberg is less decorative, and has layout problems, but supplies a distanced, ethereal quality to the series. Unfortunately his full debut is one of Gaiman’s weakest Sandman efforts, as a demented former Justice League villain, Doctor Destiny, also associated with dreams, confronts Morpheus.

At this stage Gaiman is pigeonholing himself a horror writer, and he’s not particularly good at it, although astute use of the miasmic quality of dreams adjoined to madness permits him to get away with some dreadful old tosh. “Listen to the noise Joey Campbell makes as the oven cleaner consumes his face, burns out his eyes; to the happy laughter of the little children. Listen.”

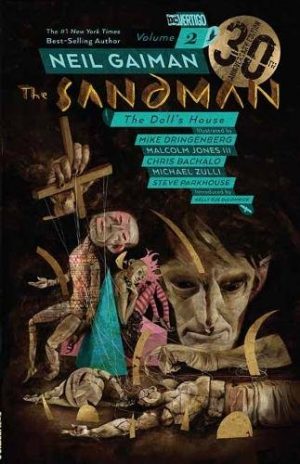

The way forward is indicated in the final and best chapter wherein a Sandman now fully back in command of his realm and vast capabilities begins the business of renewing his acquaintance with the family. There’s still some florid writing, but Gaiman’s characterisation of Death as a goth teenager in a vest is novel and interesting. So is the idea that Sandman is but one of a pantheon, the Endless, each utterly controlling an aspect of human experience with responsibilities accruing alongside that charge. Their conversation occurs as Death goes about her business, revealing much, and well choreographed. Death’s view of Dream as somewhat of a misery amuses, and sets him on the path he’ll follow into The Doll’s House.

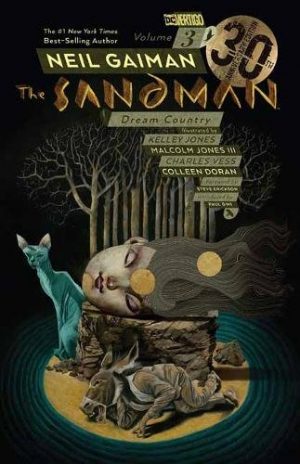

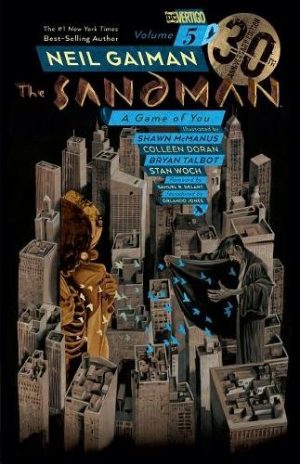

For those who’d prefer this within a package more befitting what’s considered a highlight of the medium there are two options. The oversized Absolute Sandman volume one collects this with the following Doll’s House and Dream Country in a slipcased edition. Alternatively there’s the first volume (of two) of the Sandman Omnibus, which includes all that plus A Game of You, and around half of Fables and Reflections. For those wishing to delve the hidden depths of background material, there’s also The Annotated Sandman, with the same content as the first Absolute edition, but in black and white with copious notes on a panel by panel basis explaining Gaiman’s influences, thoughts, and the ties the stories have to the wider DC Universe.

If you are concerned with the production values and can’t afford the expensive hardbacks, it’s worth springing for the current trade edition as it uses the re-mastered pages with new and improved colouring created for those editions. The earlier printings have problems with disappearing dialogue and muddy reproduction.