Review by Ian Keogh

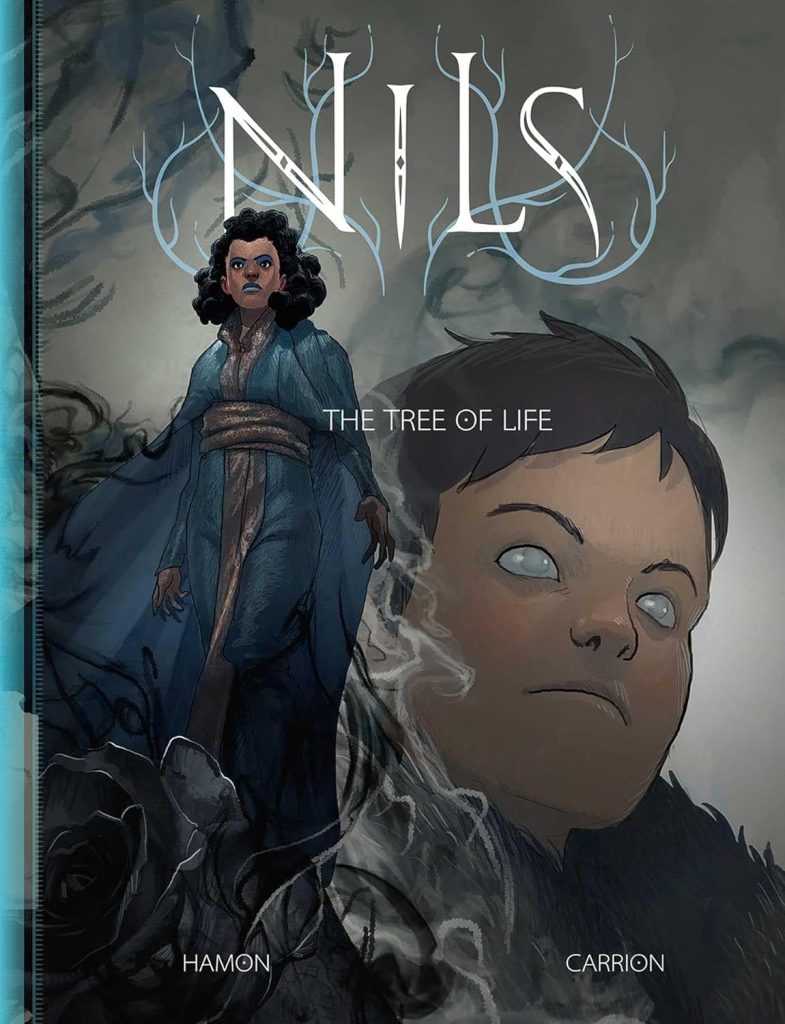

Nils is an adventurous type in a rural society seemingly afflicted by a existential crisis. Crops aren’t growing, and neither women nor animals are giving birth. At first it seems we’re looking at the distant past, but Antoine Carrion’s delicate artwork begins to show distressed architectural remains, and it’s not long before characters begin to refer to machinery, suggesting it’s best avoided. Shortly afterwards a form of spiritualism manifests via yokai, and the reason for crops not growing is deduced.

Jérôme Hamon introduces his cast as tiers, and though the initial focus, Nils and his father are the lowest ranking in terms of knowledge. We also meet a forest dwelling people, from whom Alba becomes a pivotal character, the technologically advanced Cyan people, and representatives of the gods overlooking the world. Audience sympathies are directed toward those living a simpler life, while those controlling technology use it for aggressive purposes. Hamon is aiming for the epic, and starting small to build big is a tried and trusted method of achieving that, to which he adds a sense of urgency. However, character development tends to be during clunky, explanatory monologues rather than experiences, too much revolves around beings who seem without any great purpose, and the mixing of myths from assorted cultures never moves beyond a gimmick.

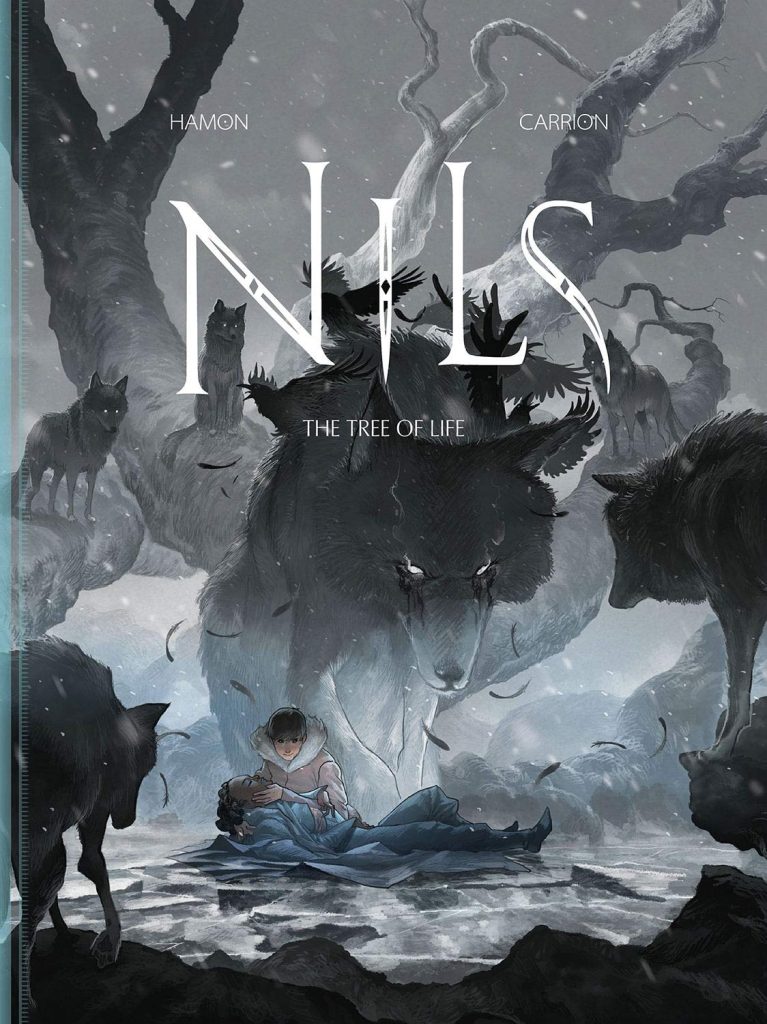

It leaves Carrion’s art as the primary selling point, and what magnificent art it is. There’s considerable effort on every page, most extremely decorative, and those that aren’t are designed to move the story forward. His weakness is ensuring the different characters can be distinguished. Hamon adds to the cast with each of what were originally three volumes in French, and telling who’s in the spotlight can require deduction as the scenes change.

A wooly and inconsistent allegory about our own use of resources develops, but Hamon has difficulty in distilling his story to the necessary elements, and the final third suffers throughout from a lack of clarity. It’s clear several points of crisis have been reached, but the solutions and outcomes are are random and ill considered. Nowhere is this more obvious than on the final pages, which makes little sense to the point where you’ll wonder if further pages are missing.

Despite misgivings, The Tree of Life was first published in English in 2020, and a 2026 reissue indicates a demand. Perhaps the art disguises many sins.