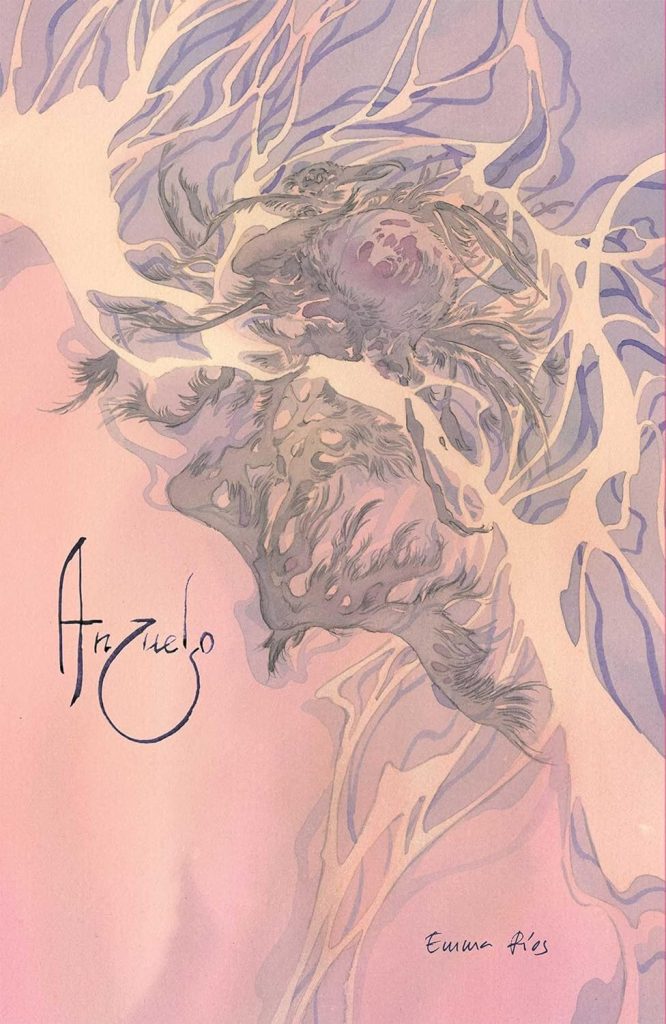

Review by Karl Verhoven

The apocalypse arrives early and surprisingly in Anzuelo, leaving three children to cope for themselves in a world the sea has taken away. Izma, Lucio and Nubero are almost immediately confronted with the unutterably strange and thrust into a new world where day to day survival is their immediate priority.

Emma Rios is better known for drawing the stories of others, but on the basis of Anzuelo that’s been time wasted. She has a unique perspective and a unique set of priorities in creating an absorbing world in an absorbing way, reflecting the experiences of the children, learning as they go along. Rios removes the certainty of pen and ink by painting the entire story in muted watercolours, and the lack of predictability about what they’ll do, even with Rios’ talent, gives a roughness to proceedings. The muted colour also plays games. Are the children really seeing the apparent strangeness, or is it in their minds? Lucio is certainly transforming, developing gills, and Nubero at one stage looks to have fallen apart and reconstituted.

Anzuelo is told via dialogue and images alone. No comforting narrative captions explain new arrivals or strange events, so perception is all. If you see something happening, it’s happened, no matter how unexpected or unconventional it is. However, that method also has its drawbacks, one being that when time jumps forward the reader can be lost until something in the dialogue indicates the change, and another being that it’s not always obvious what people are doing. As this is generally a small matter it doesn’t impair the flow.

“Why can’t ‘that thing’ care in its own way? Why should it think or feel like a human?” is a question posed at one point, and it’s central to the entire story. People are forced to confront what it means to be human. Does it mean prioritising individual survival over all else, or sacrifice for the greater good? Despite the changes to them, the children naturally fall into replicating familiar societal structures, yet due to the challenges everyone needs a function. Is this a good thing?

Rios follows the cast over a considerable period of time as they adjust from mere survival to adapting and then to ageing. There are hiccups along the way, but that’s to be expected from someone’s first writing. The ambition and the intelligence are worth a few bumps and the art is glorious.