Review by Frank Plowright

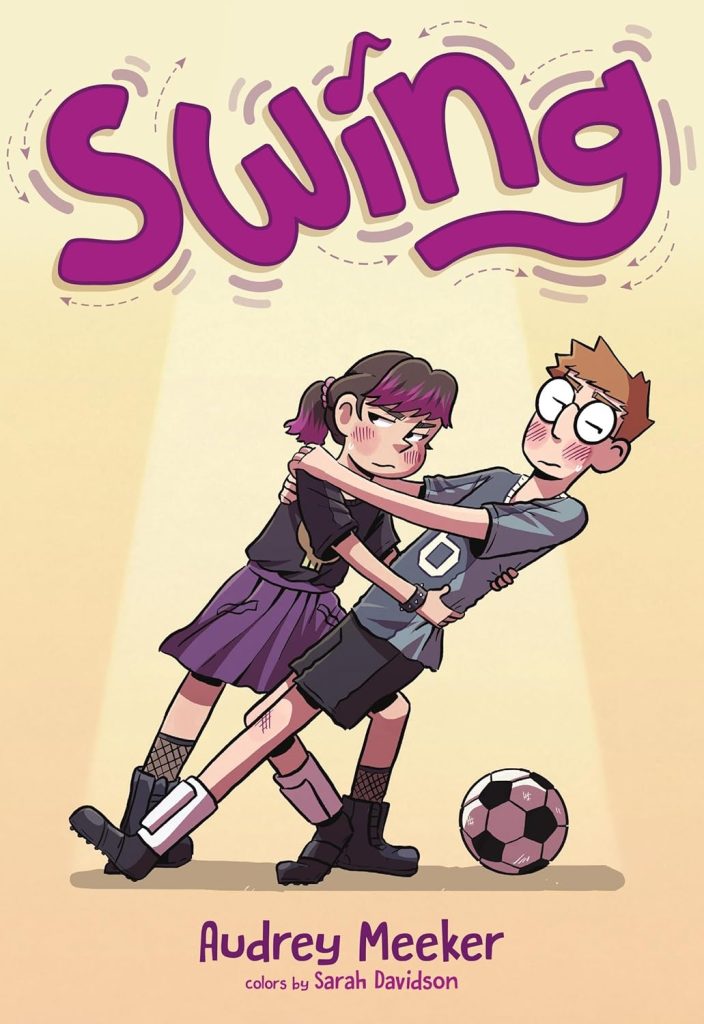

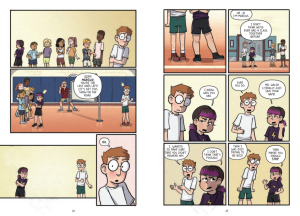

Izzy and Marcus are both now in 8th grade, and for contrasting reasons feel uncomfortable. Izzy deliberately draws comment by standing out as different, while the sparkling school reputation of his older brother hovers over Marcus and he’s unable to stand up to his overbearing and callous friend Ted. It’s a fair while before it’s revealed Izzy also has an overbearing presence in her life. She and Marcus meet when swing dance is incorporated into their gym periods, and they later find themselves together in English classes where Izzy proves smarter than Marcus. The sample art shows their excruciating first meeting.

Audrey Meeker producing both story and art enables a closer correlation between the two than is usually found in collaborations, and she spends the opening third of Swing underlining the awkwardness both characters feel, using pauses during clumsy encounters. Marcus is uncomfortable in public, while Izzy’s confident front never slips in the presence of boys. Their personalities are well developed via expressions and posture, while Meeker’s attractive cartooning also prioritises movement.

The consistent pressures both characters are under are extremely well presented, along with both feeling there’s no-one they’re able to talk to. Reflecting the internal conflicts of many less confident teenagers makes for understanding, while empowering readers who may have similar issues. They’ll see what Izzy and Marcus ought to be doing and apply that to their own lives. In this context Ted is very much a cartoon villain, skulking behind bushes and manipulating others, but he possibly has to be in order to ensure the message is relayed.

Perhaps ‘scrimmage’ is a term used for both American football and soccer in the USA, but the use will certainly confuse British readers with regard to the latter, and it underlines Meeker having greater sympathy for the well realised dance scenes than football.

As Swing progresses readers will become more and more aware than Marcus is only ever going to endure misery by hanging around with Ted. Meeker escalates the bullying to make the point that he’s going to have to stand up for himself at some stage, and the question becomes what it will take before he reaches breaking point.

Swing is aimed at younger readers, so it’s hardly a spoiler to reveal it all works out in the end, but Meeker has a novel way of ensuring that’s the case. It might have been better underlined had Ted’s eventual downfall involved school staff or parents directly, but that doesn’t diminish an engaging story about becoming independent.