Review by Karl Verhoven

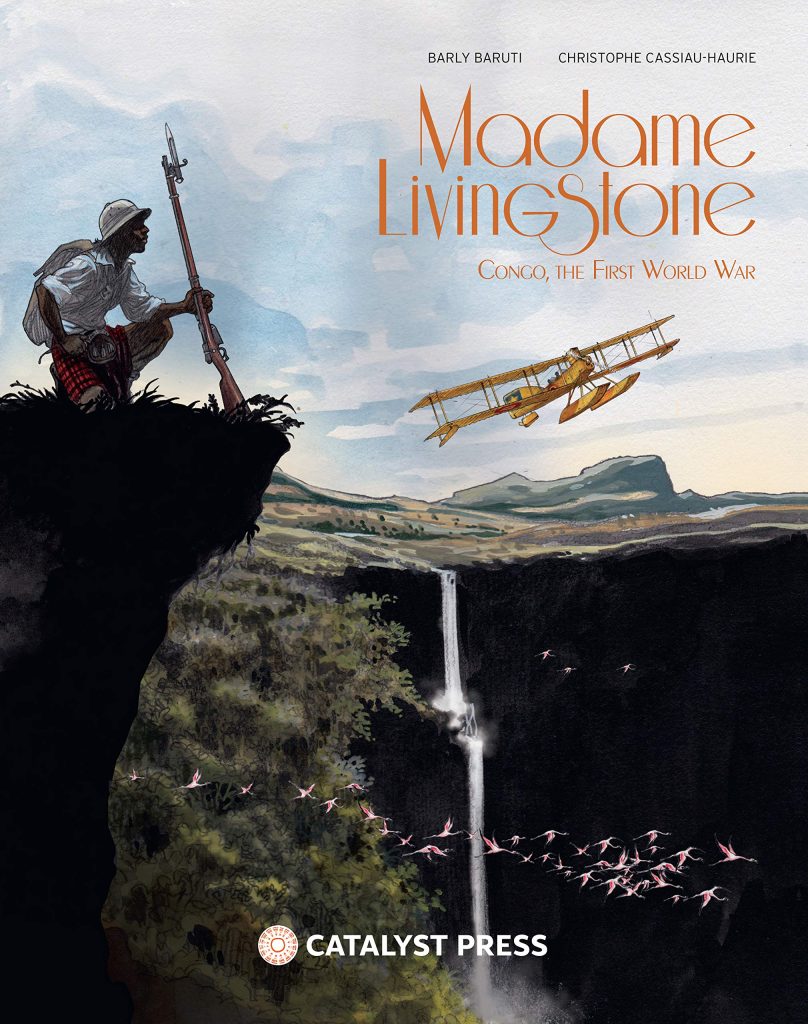

There was an upswing of creative activity commemorating World War I’s centenary, but almost all English language novels and graphic novels focussed on Europe. The war also spread to the colonial territories in Africa, and a story surely new to most English language readers is told in Madame Livingstone, originally released in France to coincide with the anniversary of the war’s start.

A foreword provides the historical background before Christophe Cassiau-Haurie begins with Belgian pilot Gaston Mercier, the means of introducing readers to Africa in 1915. The Belgians occupy Congo in Africa, infinitely vaster than their homeland, which has been invaded by Germany. Across Lake Tanganyika are Germany’s colonial territories. While Mercier doesn’t want to be in Africa, he realises being among the 700 Belgians leading 15,000 Congolese troops is preferable to the trench warfare of Europe. Despite knowing he speaks English, French and an assortment of regional languages, the derisive nickname Madame Livingstone is applied to a Congolese native for his habit of wearing a kilt. He’s a fascinating character, aware of the limited choices he has available in an occupied country, and at least has Mercier’s respect, which is just as well because there’s going to be a time when Mercier will utterly rely on Livingstone.

Artist Barly Baruti has a neat and efficient naturalistic style depicting people, and has an eye for scenery, supplying vast landscapes. In places there’s a little too much gloom at night, and in others the mix of colours seems too vibrant and clashing, but with the technology and flight Baruti really comes alive. There’s no details absent on guns, boats and cars, and the scenes of Mercier in a couple of planes when flying was in its infancy really stand out.

Because it’s so much part of the era, racism is a frequent occurrence, the Belgian officer class looking down on anyone whose skin is black regardless of their nature and capabilities. When Livingstone says “It’s the first time a white man has listened to me. Thank you.”, it’s both heartbreaking and a powerful underscoring of ignorance, as much of the success the Belgian forces achieve is down to his knowledge and advice.

The title may suggest otherwise, but Madame Livingstone falls among more realistic war stories, and the well crafted among them always carry a foreboding air of impending tragedy. Cassiau-Haurie’s version is no exception. He’s created both leading characters to be iconoclasts able to see above nationalistic concerns, and plays that out to a natural conclusion both surprising and shocking. Even more so by today’s standards is the historical documentation accompanying the research material around which the story is constructed.

Refreshingly different, and powerful in acknowledging it’s not just white guys who’re wartime heroes, Madame Livingstone reaches the parts of the conscience many other war stories don’t.