Review by Karl Verhoven

Hen Kai Pan was conceived and begun in the pre-covid era, and in his introduction Eldo Yoshimizu wonders if during covid was the right time to continue work on a graphic novel about humanity’s last gasp. “I took a walk in the nearby forest”, he explains, “and the plants looked fine. The birds looked fine. … I noticed the silence. Wouldn’t the Earth be healthier and more energetic without humans, I thought? I resumed writing Hen Kai Pan.” So, if you’re human, which applies to most readers, Hen Kai Pan isn’t the cheeriest of experiences.

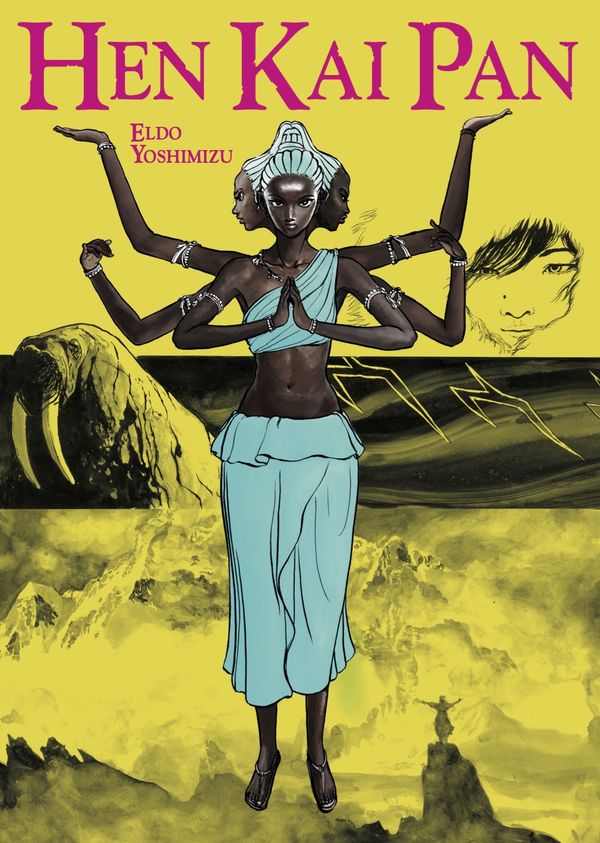

Yoshimizu takes a shorthand approach to global terrorism, personifying it in Nila, whose unthinkingly obedient catspaw Asura carries out atrocities on her behalf. Nila is wonderfully presented by Yoshimizu, as a creepy, exaggerated villain, seen giving instructions while playing an organ, the crescendos in the reader’s mind. However, there’s much to be discovered about Asura and Nila, as there is about Earth itself, and several guardians.

While framed as an action thriller, Yoshimizu has serious points to make about humanity’s pollution, not just industrial, but down to personal problems such as littering. The message is that we’re individually responsible, although that ignores the scale, and that being the case if the planet is viewed as a living entity, what’s to be done? Yoshimizu teases, but the answer’s there in his introduction. Humanity’s fate plays out as a discussion among immortal representatives with occasional detour into battles.

The illustration is stunning. Given the topic at hand and his view on it, Yoshimizu produces page after page of nature at its most impressive, ramming home what’s being neglected and destroyed. Theoretical arguments eventually play out against scenes of continual destruction, sometimes abstracted, sometimes hitting with the impact of a punch to the face. However, Yoshimizu isn’t the most organised at presenting his concepts, and Hen Kai Pan veers between the straightforward and the puzzling, both in tone and visual metaphors. There’s no problem in understanding the overall message, but some of the finer points may be lost.

In the final knockings, though, there’s a neat solution to humanity’s infestation, with Yoshimizu of the view that the path is set, and humanity’s greed will always overcome common sense. It’s not comfort reading, but Yoshimizu’s sincerity and own concerns transmit strongly, and you’re likely to find yourself staring at individual pages, and considering what can be done.