Review by Frank Plowright

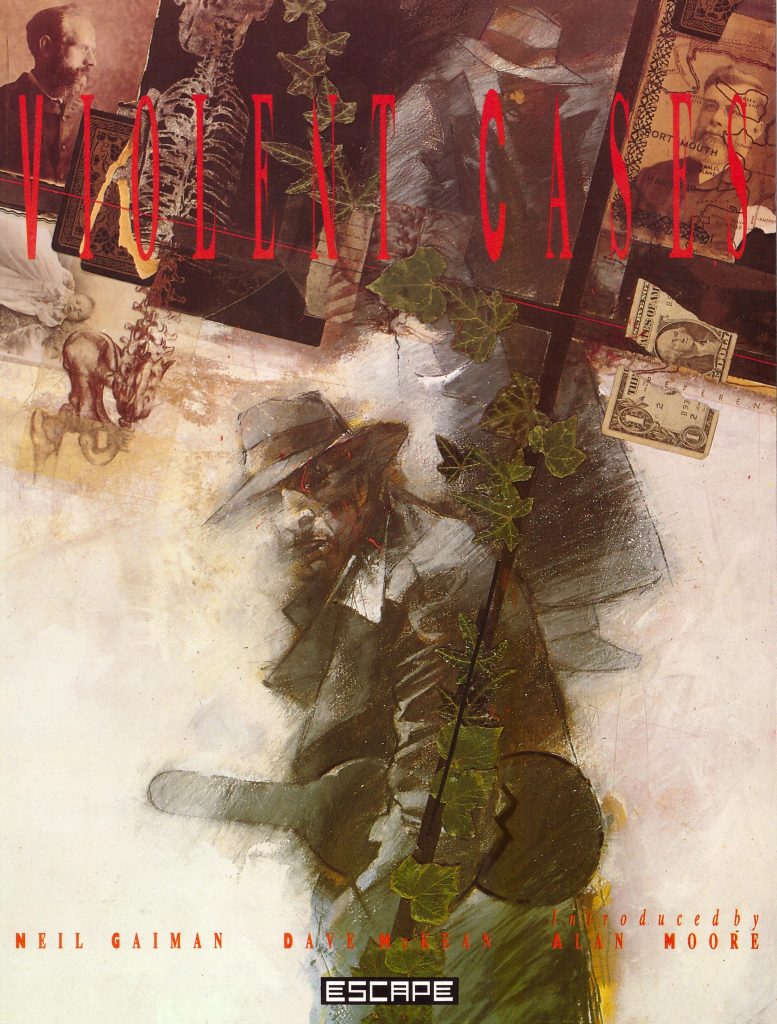

Violent Cases stands as a marker for how the sophistication of graphic novels has accelerated since the 1980s. In his introduction to the original 1987 publication Alan Moore mentions the perception of this, noting how the definition of comics had grown to encompass relative substance, and citing the work of then newcomers Neil Gaiman and Dave McKean as an example. It now reads as very mannered. That’s partly to do with Gaiman adapting from a short story he’d written, but making little in the way of concessions for a different format. Dialogue is presented in caption boxes along with descriptions and observations, and McKean’s illustrations hover and suggest, incorporating the fine art techniques he’d later distil more effectively during his rapid artistic progression.

This, however, doesn’t give enough credit for Violent Cases being the work of two novice creators. Moore provided Gaiman with pointers, but the voice is his own. Equally, while much of the artistic technique owes a debt to the contemporary work of Bill Sienkiewicz, the storytelling and imagery is down to McKean, and it should be noted that very few comic artists in 1987 could approach the stylistic complexity of Sienkiewicz’s work. McKean takes one of the themes being the imprecision of childhood recollection and runs with it, providing appropriately sketchy art that fades in and out. Originally in black and white, McKean added some touches of colour for Titan’s 30th anniversary hardcover reprint, but these are impressionistic and subtle.

Gaiman’s concern is the frailty of memory and a child’s capacity for attempting to construct logic where there may be none. He takes the role of narrator, recalling how a childhood injury led to a meeting with an osteopath once employed by Al Capone, the man resident in Portsmouth on England’s south coast since the end of World War II. The practitioner’s revelation leads to a string of explanations fascinating the child, as he’s also occupied with thoughts of dressing up to attend a fifth birthday party. Some themes here recur frequently in Gaiman’s subsequent work, including the notion of barely perceptible magic, the blending of fantasy and reality, children coping with an adult world of concealed mystery, and poor parenting. How much is intended to be taken at face value? The adult Gaiman illustrated throughout wouldn’t have been recognisable to many readers in 1987, so is this Gaiman the storyteller whimsically illustrated by McKean, or is it a form of autobiographical recollection?

While an excellent if considered as a first work, it’s by two talented creators whose ultimate fame spread far wider than comics, and on its thirtieth birthday Violent Cases lacks engagement. The distanced narrative is more responsible than the art, unconvincing as more than a stitched together yarn produced as an experimental exercise, with the central conceit not withstanding a moment’s scrutiny as it’s never clarified. While Gaiman can never be labelled as a literalist, the recollections are neither nailed as the playful ramblings of a barfly or given substance. Al Capone had an oesteopath? Really? Don’t buy this on the basis of Gaiman’s later work. It’s a spirited début, but a curiosity now.