Review by Graham Johnstone

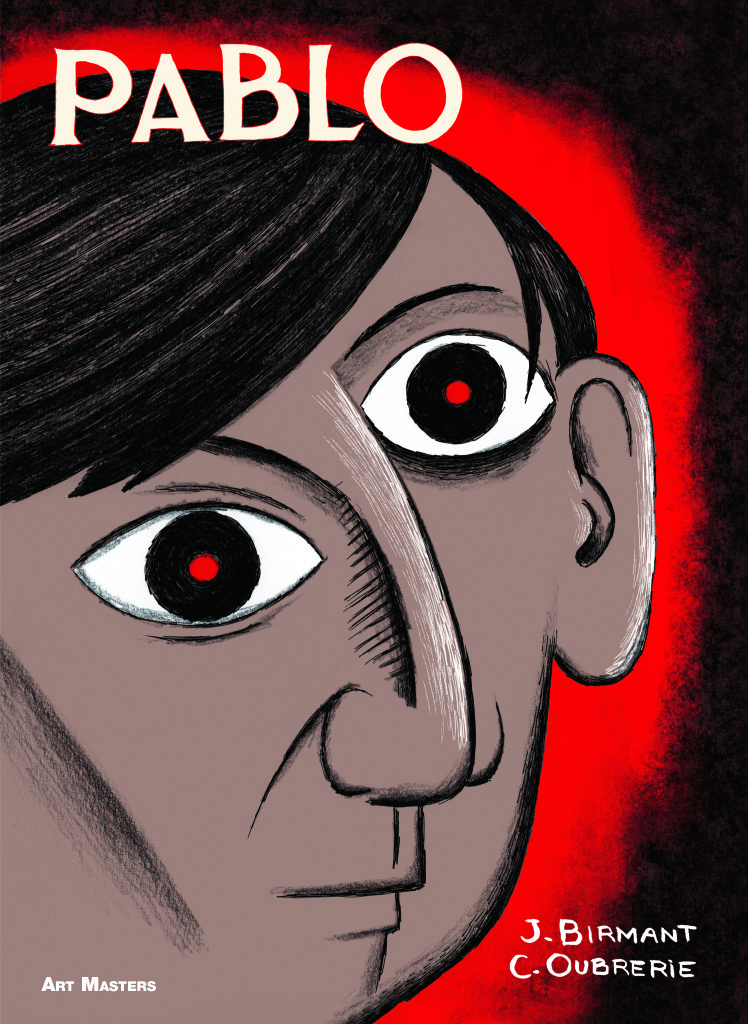

One look at the cover confirms that the Pablo in question is indeed Picasso: there’s no mistaking his depiction of faces in composite frontal/profile view, or indeed the artist’s powerful dark eyes.

Inside the cover, it’s initially disappointing that the artwork doesn’t reflect Picasso’s famous style. However, Pablo focusses on the early years – what are now referred to as the Blue and Rose periods – and the art reflects that.

Another fact not signalled on the cover, is that this is as much the story of Fernande Olivier, Pablo’s lover at the time. The book starts with her, and she’s the narrative voice of the (admittedly few) captions. Perhaps this is why the focus is less on the creation of Picasso’s paintings than the man himself: the sensual lover, charismatic friend, driven rival, and sometimes troubled soul.

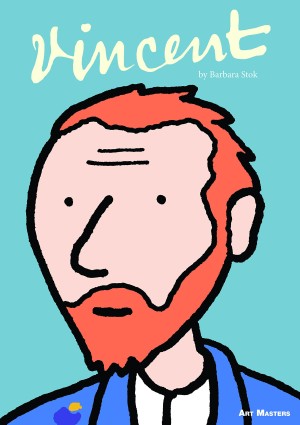

Following Vincent, this is the second in SelfMadeHero’s Art Masters series, and again, a first English translation. It gathers Julie Birmant and Clément Oubrerie’s four French albums into this hefty, but affordable volume. Starting with his arrival in Paris, it ends a mere seven years later, as he rips up the rule book with Les Demoiselles D’Avignon.

It’s an ideal introduction to Picasso and his world, and, for those with some prior knowledge, a spotters delight – we meet the poets, artists, impresarios and taste-makers who would inspire and support him. Gertrude Stein (not yet a famous writer) commissions a portrait. Matisse, the creator of strikingly joyful art, is a stern patrician in a top hat – addressed as ‘Master’ by his followers. Derain, Vlaminck and Braque, though, shift allegiance to Picasso, but when they start calling him master, he mocks and avoids them, eventually chasing them off with gun-shots into the air. Scenes with poets Max Jacob and Apollinaire capture the excitement of creative minds fuelling each other.

We also see the darker pivotal moments, like the suicide of a painter friend, which in turn triggers memories of his little sister’s death. We’re shown an immediate effect on Pablo, but Birmant doesn’t attempt to trail this into later events. In fact, Pablo would, literally and figuratively paint his tragic friend over the years of his melancholy Blue Period. We’re also shown Pablo’s smothering over-protectiveness with Fernande. Readers might link this to feelings of guilt and failure over his sister’s death, but Birmant avoids such speculation.

Oubrerie nails the famous faces, and real-life settings. Like Picasso, his stylised figures focus on expression over exactitude. He tones his scratchy line drawings with ink washes and charcoal. Sandra Desmazières adds sympathetic colour washes, but over such heavy tones it can look murky and oversaturated. That may be partly the printing though, as screen images from the French editions are far more vibrant. In any one panel the colour may be almost monochrome, though generally evoking the Blue or Rose palettes.

Their thoroughness in documenting Picasso’s life is double edged, though. It does at times feel too long. It may have helped if SelfMadeHero had recognised the original four parts – it would have given a sense of structure, and some stopping off points in this now chapterless 340 page tome. That’s nearly a typical French album’s page-count per Picasso year – surely enough space to have explored his creative processes more, and further highlighted the ways the talented people around him actually shaped his work?

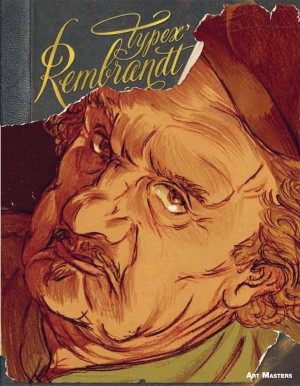

Picasso is a towering figure in modern art, and caveats aside, this boldly ambitious project succeeds as both accessible introduction, and serious biography. Next in the series is the better still Rembrandt by Typex, with Kverneland’s Munch to follow.