Review by Ian Keogh

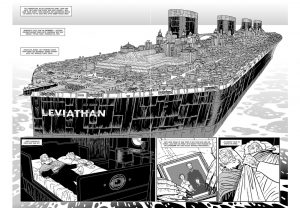

In 1928 Leviathan, the largest ocean liner ever constructed leaves Britain on a cruise. It’s the equivalent of a floating city, and twenty years later it hasn’t returned. It’s still afloat, just without any way home. However, for all the fripperies such as a zoo onboard, it was only ever supplied with enough provisions to sustain passengers for a single voyage, albeit in luxury. Yet why is it that the ship hasn’t run out of fuel? The second class lower decks have long devolved into anarchy, but now there are also killings occurring in first class, horrifying deaths in which the skin is flayed from the body. Fortunately among the crew is Detective Sergeant Aurelius Lament of Scotland Yard.

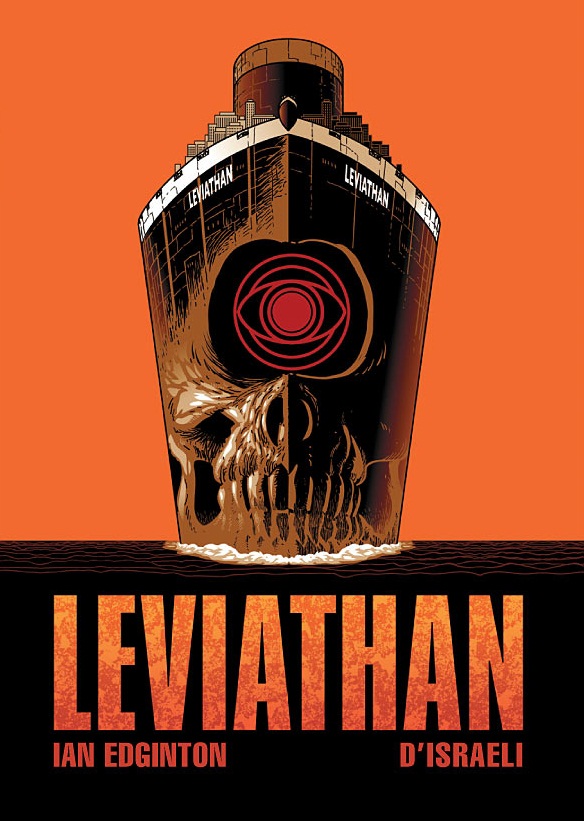

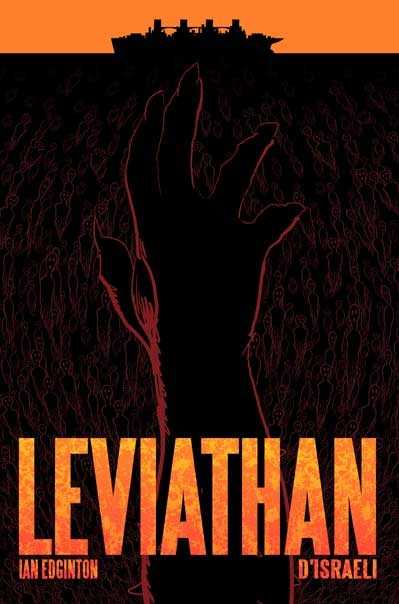

It’s fundamental to Ian Edginton both setting his mood and defining the near impossibility of Lament’s task that there’s an exploitation of Leviathan’s sheer scale, and D’Israeli’s intelligent art establishes that from the very beginning (see sample spread). He continues to underline this with illustrations showing people as almost dots within the vastness of their environment, and that’s in addition to some great character designs, the formality appropriate to the period. He also needs to convince with the main threat, referred to as stokers, and our first view of one as it commits murder is a soul shuddering illustration. There’s even worse, though. Further notable is D’Israeli’s use of grey lines to accompany the black and white, giving the entire project a distinct look.

Edginton exploits the British class system of the era well, and succeeds in having Lament live up to his name. He’s resourceful, brave and not easily startled, but a dour companion. That’s exactly the type of person needed, however, to process the eventual revelations, as Edginton has a far wider brief than just the ship. He’s weaved a classic horror story, hitting all the right notes and Leviathan provides a unique location for his scenario to play out.

The core story is complete in just under sixty pages, and these comprised the graphic novel when first issued, but subsequent editions include later and shorter stories. It’s sometimes the case that everything that needs to be said has been said, and returning to nip and tuck is a mistake, but not here. Edginton and D’Israeli are both on board for the sequels, and the first of them addresses a question that the astute reader might have had hanging, spelling things out clearly and concisely. The shock of the unknown is absent, but this is good. So are the remainder. They’re more along the lines of the sting in the tail ‘Future Shocks’ that 2000AD has used as tryouts for new creators since the early 1980s, but these are being created by two experienced creators at the top of their game. ‘Captain’s Log’ the final one, is a particular gem, just three spreads dated 1928, 1929 and 1948, the logbook open on a desk with the surrounding junk changing each time. The devil is in the detail here. Edginton and D’Israeli have been playful about bit part names throughout, and are again.

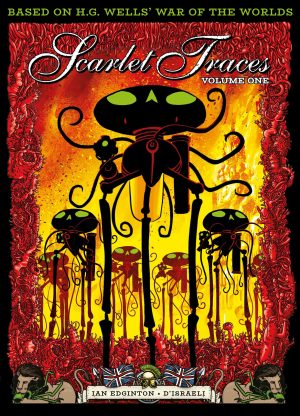

Rounding off the collection are D’Israeli’s design sketches, accompanied by comments, and Edginton’s script for the first episode, showing him responsible for a fine visual effect on the opening pages. He’d had plenty of time to refine it, having had no takers when he touted it around in the 1990s, which seems incredible on reading it. Any collaboration between Edginton and D’Israeli is worth your time (see recommendations) and anyone who enjoys a good horror story is missing out if Leviathan’s not on their shelf or hard drive.