Review by Frank Plowright

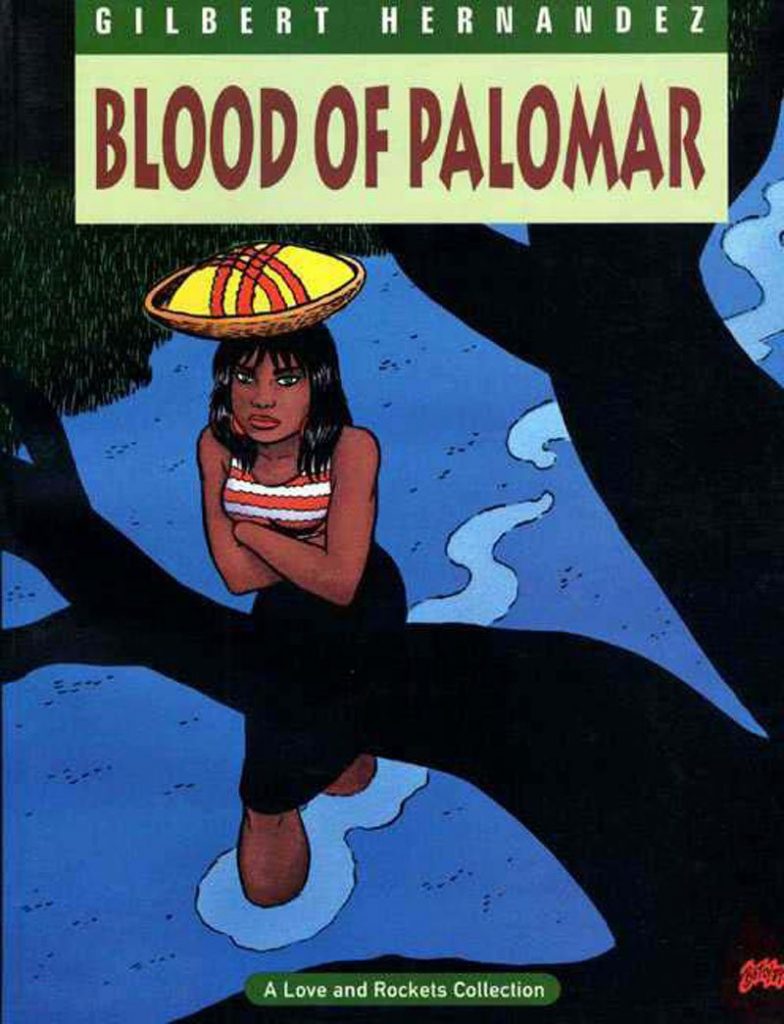

Despite a double meaning, Blood of Palomar is an inappropriately lurid title for what is Gilbert Hernandez’s masterpiece, the story where he fully realised his ambition to master the rich storytelling and emotional depth of Gabriel Garcia Marquez. It builds on relationships, secrets and events disclosed in earlier Palomar stories to trawl through the personalities of the cast, testing them and pulling them into turmoil.

Almost every major character previously introduced is run through the mill, down to Luba’s children. Luba, always putting herself first, doesn’t approve of how her eldest daughter Maricela is now dressing, not least because her figure is beginning to resemble the younger Luba. She’s further reminded of that because Khamo, the only man she’s truly loved, and father to two of her daughters, is working nearby. The easily influenced Tonantsín has fallen under the sway of a jailed pseudo-revolutionary, an infestation of monkeys is becoming an increasing nuisance, and that’s before a body is discovered.

This isn’t a murder mystery, not least because the attentive reader will realise the killer’s been named even before Hernandez reveals him soon after we become aware there’s been a murder. He’s more interested on the disruptive effect the murders and other events have on Palomar as a community. Tonantsín’s mental health has always been fragile, Luba’s unreasonable behaviour has an effect on her children, Humberto’s prodigious artistic talent takes ever more abstract turns and town secret after town secret receives an airing. The moods switch mercurially, along with the symbolism, and for what’s largely a tragic series of events there’s also a lot to laugh about, from the fatally attractive Khamo never actually given a line of dialogue to the eventual reappearance of what just seemed to be a ridiculous prop, exaggerated for effect.

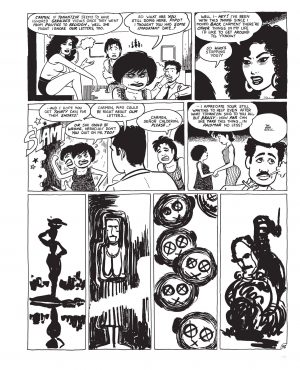

A visual richness equals the evocative character building, Hernandez dazzling with expressions and poses, the cast leaping from the pages. As seen on the sample art, he’s able to slip from poised cartooning into representational primitivism and almost abstract sketching, all heavy on the black ink. Fundamental events are told without dialogue, Hernandez now completely trusting his own talent.

Such is the abundance of fine moments, it’s possible to notice something new about this story every time it’s read, no matter how many previous readings there have been. It might be a simple expression giving something away, or beautifully crafted cinematic juxtaposition, or a panel that may or may not be symbolic. Even if known, the heartbreaking foreshadowing moment is still powerful, and since 2001 the use of New York’s twin towers provides completely unintended foreshadowing of the final tragedy. The closing masterful touch is this occurring to the self-absorbed commentary of the person who prompted the path. However, those final scenes is lose considerable impact for readers who’ve not read ‘Heartbreak Soup’ and a story featured in Duck Feet, as they cleverly reference events without explanation. Don’t worry about that, though, as this all-pervasive cyclone of human feeling is a highpoint not just for Hernandez, but for graphic novels altogether. It’s essential.

In the UK Blood of Palomar was issued under Hernandez’s changed title of Human Diastrophism, substituting one unsuitable title for another, that being plain pretentious. A Fantagraphics collection titled Human Diastrophism was issued in 2007, including a large quantity of additional Palomar stories. Most of those along with earlier material is also found in the hardcover Palomar collection, also containing most of the content from the following Luba Conquers the World.