Review by Frank Plowright

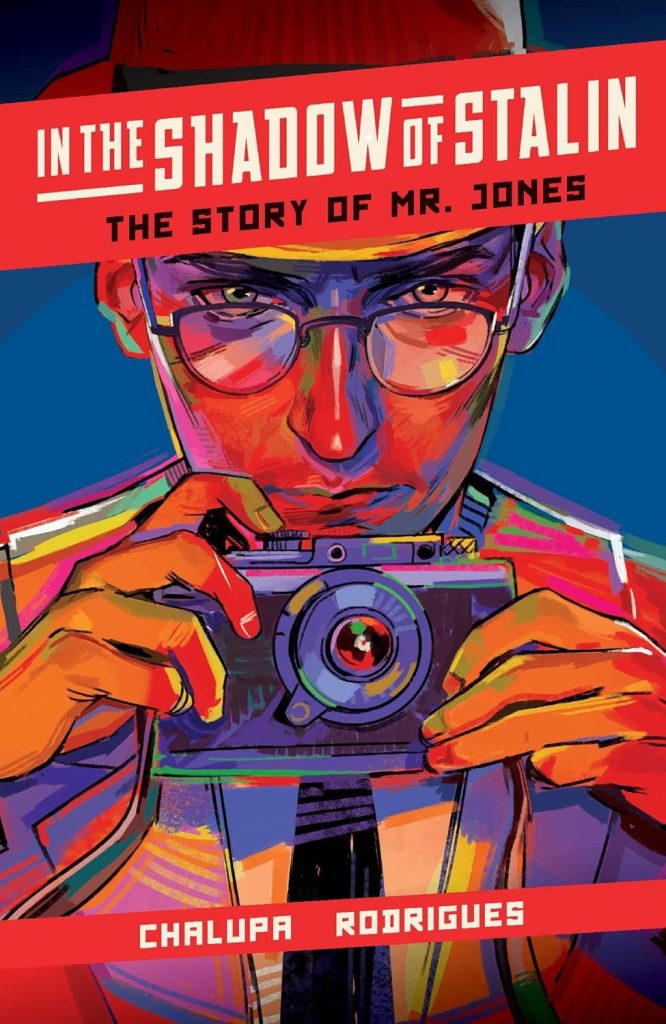

Almost a century after it occurred, the previously little known events of Ukraine’s 1930s famine are again being brought to the wider world. Red Harvest tells the story of this entirely avoidable humanitarian tragedy from the view of ordinary people, while the 2019 film Mr. Jones concerns the journalist who first brought matters to the attention of the wider world. It was made by Andrea Chalupa, who revisits her research with what plays out as an investigative dramatisation of Welsh writer Gareth Jones attempting to tell the world the truth.

The opening is startling enough. As a parliamentary advisor Jones has been sent to Germany in 1933 and found himself on a plane with Adolf Hitler and several other high ranking Nazis. They boasted to him of their plans, yet Jones was considered gullible when he reported back to those running the UK. When he’s made redundant, he determines to visit Russia, his initial ambition being to interview the leader of the Soviet Union since 1924, impressed at how rapidly Stalin is increasing manufacturing. Jones’ starting point is to wonder how he’s paying for it, and that curiosity eventually reveals a horror.

Such are the layers of secrecy in Moscow and uncertain allegiances of the foreigners there, Jones treads a precarious path, and has to do so within the stringent limits set by the Soviet state. As not many people know the story Chalupa’s telling, it generates an abiding tension as to how Jones is endangering his life.

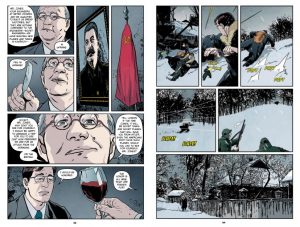

Ivan Rodrigues is an artist good at drawing people, which is just as well. Due to the cloak and dagger nature of events, In the Shadow of Stalin is heavy on conversation, and it limits the possibilities, although Rodrigues doesn’t make the most of what he’s given. Drawing people in close up is easier than showing conversations from a distance in fully rendered rooms, but it also reduces the art’s appeal. When Jones heads into the Ukrainian countryside he witnesses starvation, desperation and other horrors, and the change from urban to rural environments requires greater visual variety. Rodrigues shines here, supplying a gritty realism to signify the changed tone.

Jones’ form of idealism is contrasted well with an American journalist deluding himself he serves the greater cause of world peace by never challenging Soviet propaganda, but Chalupa might have supplied more information on the Ukranian famine. In Ukraine it’s known as Holodomor and still commemorated every year. Until the end notes In the Shadow of Stalin never makes it explicit that Stalin’s expansion programme was funded by selling Ukranian grown wheat abroad while the farming communities starved. The fight Jones had to cut through political interests is important and well told, but the information not supplied was needed to complete the connection between expansion and starvation.

Overall, though, Jones’ work, although sensational at the time, has slipped through the cracks of history. His bravery and persistence deserves to be more widely known, and In the Shadow of Stalin presents the truth as he’d have surely wanted it.