Review by Frank Plowright

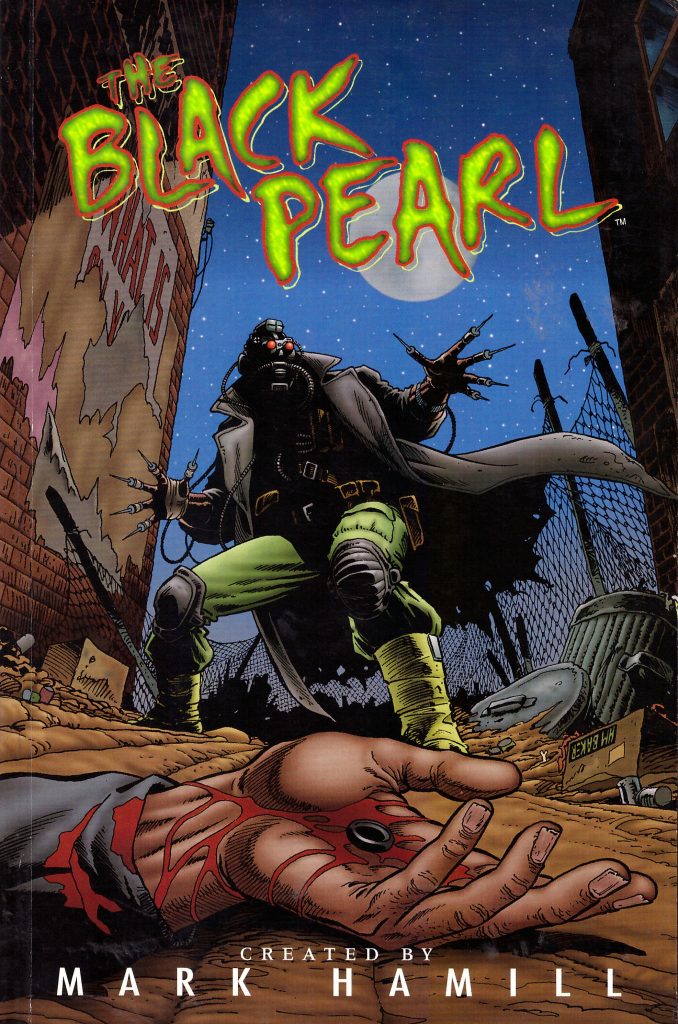

Publishers eventually learned that involving celebrities with graphic novels didn’t produce the anticipated sales and the resulting book was rarely a creative success. The Black Pearl isn’t one of those. Mark Hammill has something to say, and he and co-writer Eric Johnson weave a compelling story around his comments on news programmes and how the deciet and egos behind them shape what we believe. If anything, it’s even more relevant now than in 1997.

Luther Drake is hardly a beacon of virtuosity. He trains his telescope on the bedroom window of the attractive woman who lives opposite, and is, in effect, stalking her when she’s abducted by others. His entirely accidental intervention doesn’t prevent the kidnapping, but leaves one of the criminals dead. Grainy footage of his escape is filmed by a pair of TV news journalists who intend to investigate further, but before they can do so the footage is hijacked by unscrupulous presenter Jerry Delman, and aired in sensationalist fashion. Delman names the Black Pearl, and Luther constructs an identity based on what was presented on TV.

At its core The Black Pearl concerns lack of restraint on the part of two people unable to stop what they’re doing. Luther and Delman have different motivations, but each is a long way from pure. Delman considers promoting the Black Pearl will kickstart a failing career, and Luther has plenty of unsavoury habits. Each continues along a path that eventually collides at a public event organised by Delman, celebrating the Black Pearl. Caught in the middle are the two upright journalists and the kidnap victim, whose story unfolds.

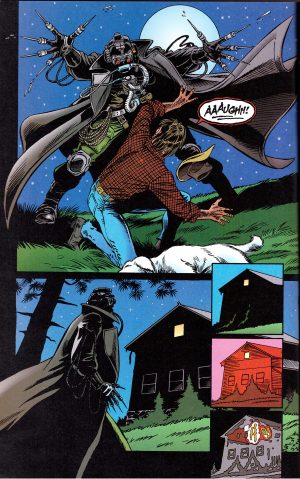

Artist H.M. Baker designs a complex costume for Luther, convincingly resembling something that could be cobbled together by someone with some scientific know-how and access to materials. The same busy approach informs his pages. Houses have the touches that show they’re occupied, and people obviously work in his offices. His attention to detail blossoms in a double page spread set at Delman’s event, where he not only draws over two dozen foreground figures, he follows up with even more in the middle ground before resorting to outlines to show thousands more. The downside is that his faces aren’t always consistent from panel to panel, although as all the main cast are easily differentiated by hair style and clothing this isn’t fatal.

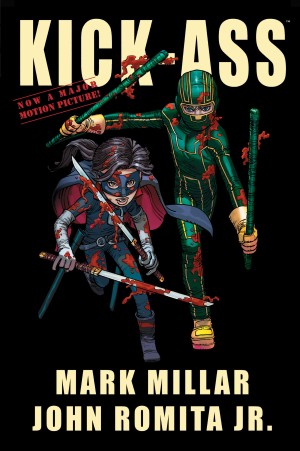

Hammill and Johnson set up the ethical clashes well, and they characterise in shades of grey. Even the largely pure hearted journalists have no qualms about breaking and entering to further their story, or withholding evidence from the police, and this moral muddiness serves the plot well and ensures it’s not dated since the mid-1990s. In the years since publication, deliberately inflammatory and offensive radio and TV presenters of Delman’s type have multiplied as there’s always a market for outrage, so he’s a very contemporary figure, and Luther pre-dated Kick-Ass by a decade. However, the plot doesn’t hold together until the very end, and the final chapter betrays the needs of a film script for a resolution that’s just too tidy.

Overall? A lot of fun, but as far as the fates of the cast are concerned it descends into Hollywood.