Review by Karl Verhoven

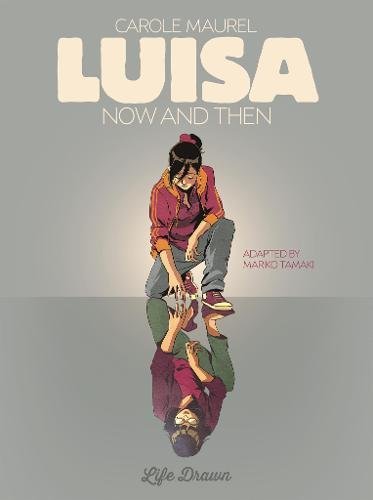

Sixteen year old Luisa Arambol has a problem. She fell asleep on a bus in 1995 and woke up in 2013, transitioning from a world where the French currency was francs, and phone cards were essential to one of cellphones and Euros. She’s still alive in 2016, having inherited her Aunt’s Parisian apartment, and is none too keen to have her younger, less knowing self turn up.

Humanoids have taken an interesting approach to translating Carole Maurel’s story, commissioning a translation from Nanette McGuinness, before having Mariko Tamaki provide the dialogue. It’s a viable move, as with her own output Tamaki has shown a propensity for being in touch with her younger self, and while Maurel’s illustration is evocative and open, Tamaki gives the younger Luisa authenticity. The older Lisa is more complex. Maurel presents someone unhappy at the way her life has turned out, whose ambitions remain unfulfilled, and now has a mirror held up to her of a time when life held possibilities.

Maurel deliberately sidesteps obvious comic possibilities, while still allowing the younger Luisa to confront older versions of her friends with what they once were, far fresher in her memory. “If you say ‘waste’ again talking about my job, my life or my kids I’ll hook your earrings onto your scrunchie and make you eat them to wash down all that judging” is the older version one friend’s response. While the reason for her appearance in the present of 2013 isn’t spelled out, it’s hinted at, but a weakness is the elder Luisa insisting on keeping the truth concealed, resulting in moments of furtive avoidance out of place in a larglely naturalistic drama. Ultimately this is a coming of age story, but the unusual aspect is that it’s for the older Luisa, eventually freed to define who she is, and deal with the causes of her repression. It’s a confrontational process and the idea that someone’s younger self is the only person capable of forcing the truth on them is nice, as is the dialogue Tamaki provides for these scenes. How Maurel weaves the past into 2013 is notable. The younger Luisa has just been barred from seeing someone she likes by her homophobic mother, and that incident has been key in shaping the older Lisa’s unfulfilled personality, which in turn has held her back.

When it comes to expressions and emotion Maurel’s art is ideal, but she’s not as strong at designing a page. It’s highlighted because Maurel’s storytelling is very leisurely, taking time to set a scene, and including several that don’t add much to the plot, such as Luisa’s neighbour Sasha on her walking trip. There are times when greater haste would be beneficial, but weighed against the positive messages Luisa presents that’s a minor complaint.

There are many conflicted youngsters who could benefit from reading Luisa, so let’s hope it reaches a few of them.