Review by Ian Keogh

When Nick Cave wrote ten songs about killing and issued them as the Murder Ballads album in 1996 he was bringing an old country tradition to a wider audience. Musical stories of murder were handed down through the generations long before the advent of recorded music, provided as both a warning that stuck in the head, and spine-tingling entertainment, and Cave isn’t the only living musician to have dabbled in the genre, although did so extensively.

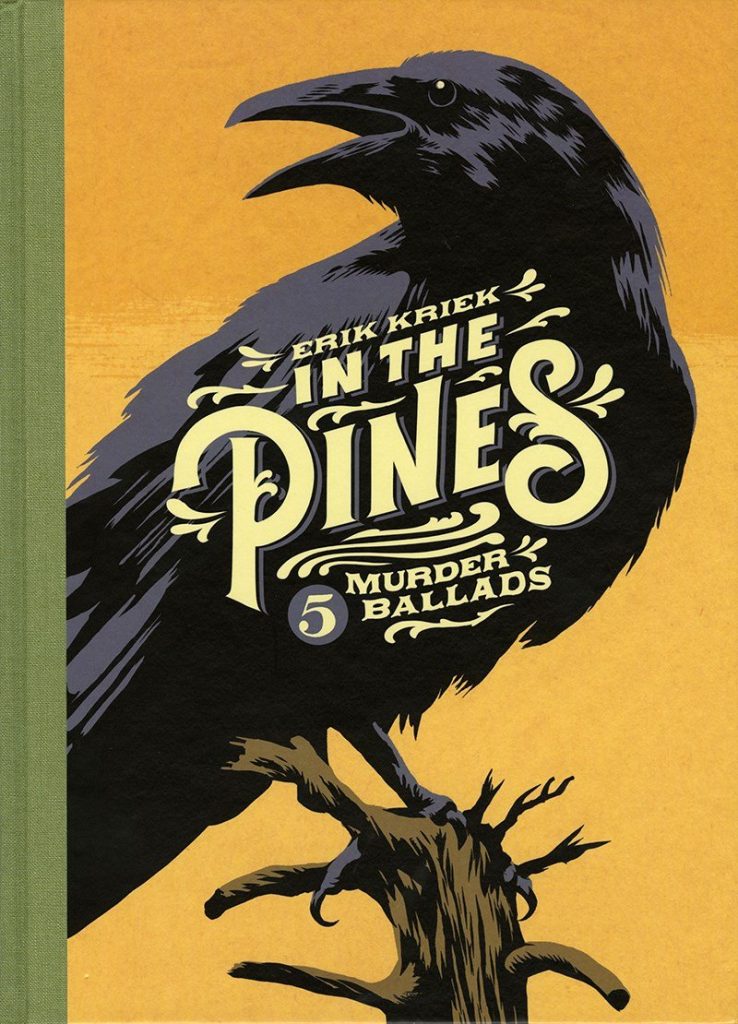

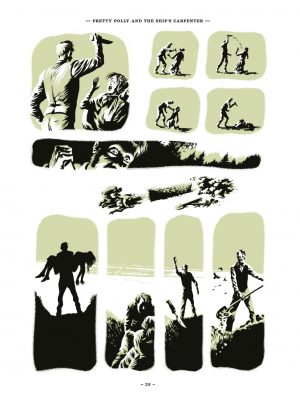

Murder ballads entertain and horrify equally, and the one essential element is atmosphere. You’ve got to believe the creative voice, and In the Pines provides the mood in spades. As songs, the lyrical content is necessarily brief and Erik Kriek fleshes out the bare bones of those lyrics providing an intensity to horrific deeds, although the killer is in several tales the most sympathetic character, and Kriek rarely shies from displaying the mental cost. He also extemporises on the source material. This is apparent from the opening Pretty Polly and the Ship’s Carpenter, the only song adapted pre-dating the 20th century. In its original form it’s a relatively traditional tale of murder, passion and ghostly revenge. Dispensing with the linear portrayal, Kriek shifts back and forth through time and adds his own homage to a latter day horror classic. It’s a perfectly legitimate device. Until the advent of recording technology the singer controlled the song, and numerous variations are known of Pretty Polly and its imagery of a haunted ship.

Kriek works in black and white with a different additional colour for every chapter, and his dense, almost woodcut style establishes an era and mood in what’s otherwise a very cinematic style. His incorporation of surroundings and wildlife is very effective, cutting back from the protagonist for moments of contemplation and in itself very decorative, as are his evocations of small towns and the rogues they house.

The Long Black Veil was popularised by Lefty Frizell in an overly lugubrious fashion, but Johnny Cash’s is otherwise probably the best known version of a powerful tale of a man who’d rather be hung for a murder he didn’t commit than betray a friend, in public at least. Kriek’s modification adds a effective afterthought on passion and betrayal, and transposes a lyrical element from Steve Earle’s Taneytown, the following adaptation. Kriek makes a considerable number of additions, focusing on the murder weapon and following its history in a lengthy prologue prior to moving onto an almost straight reading of Earle’s lyrics.

Caleb Meyer is the most recent work, released by Gillian Welch in 1998, but much covered since. It’s short and perfectly formed, but results in the collection’s weakest story as the dramatic concerns Kriek adds of hopes for the future don’t set anticipation of events, and dilute what was originally a short, sharp shock. Cave’s Where the Wild Roses Grow provides only the bare bones for Kriek’s story, which takes its own route inspired by the title, and this is far more effective, surprising and providing a shocking answer to a question posed in the song. It’s an almost perfect slab of murderous melodrama.

Considering he takes his title from it, it’s a shame there’s no adaptation of In the Pines, first recorded by Leadbelly, but it makes for an evocative mood-setter if you’re familiar with it. There’s a graphic emotional intensity to In the Pines that thrills the darkness we all carry within. Succumb.