Review by Graham Johnstone

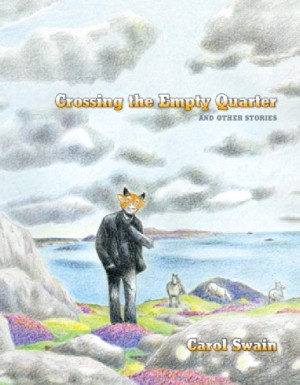

Trained as a painter, Carol Swain was inspired by the UK’s vibrant small press comics scene of the 1980s, and went on to create some of its most memorable works. 2004’s Foodboy was only her second book release, though a retrospective selection of her shorts was eventually released as Crossing the Empty Quarter.

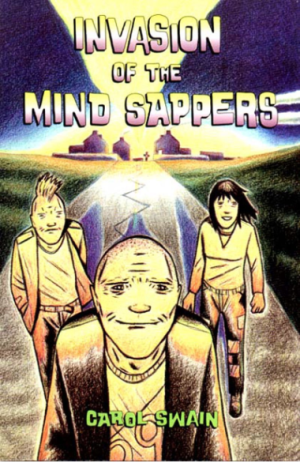

Foodboy, while complete in itself, forms a loose trilogy with the earlier Invasion of the Mind Sappers, and later Gast. They’re all set in the fictional village of Llanparc in rural Wales. The decline of it’s mining and related metallurgical industries left Wales with high unemployment, which left many young people with a stark choice: leave home or have no career prospects. That’s the backdrop to much of Swain’s work, including this story of Ross, who ‘opts out’ of the official world.

The story is told from the point of view of Gareth, who sustains his friendship with the increasingly distant Ross, and supports him with food packages. Swain powerfully, and poignantly refutes the crude idea that people are poor through their own fault or failings as this pair are bright, articulate, poetic young men, with a critique of society and it’s institutions, yet with their own vision and aspirations. In different circumstances they would have flourished, and Ross might have led a positive social movement, instead of, well, a cult. Like the earlier book with it’s apparent alien presence, the theme is young people trying to imagine and realise an alternative – even if it’s an extreme one.

In an early scene travelling preachers are in town, and decry Llanparc as a modern Sodom and Gomorrah. Having listened to this, Ross very politely asks that the preacher now listen to him, and what he, Ross, believes. The preacher agrees, mockingly setting him up – Ross’s response is assertive silence. What does this mean? Swain avoids over-explanation, but it seems to say “Here’s what I think the church, the government, the world, has provided for us: nothing!”.

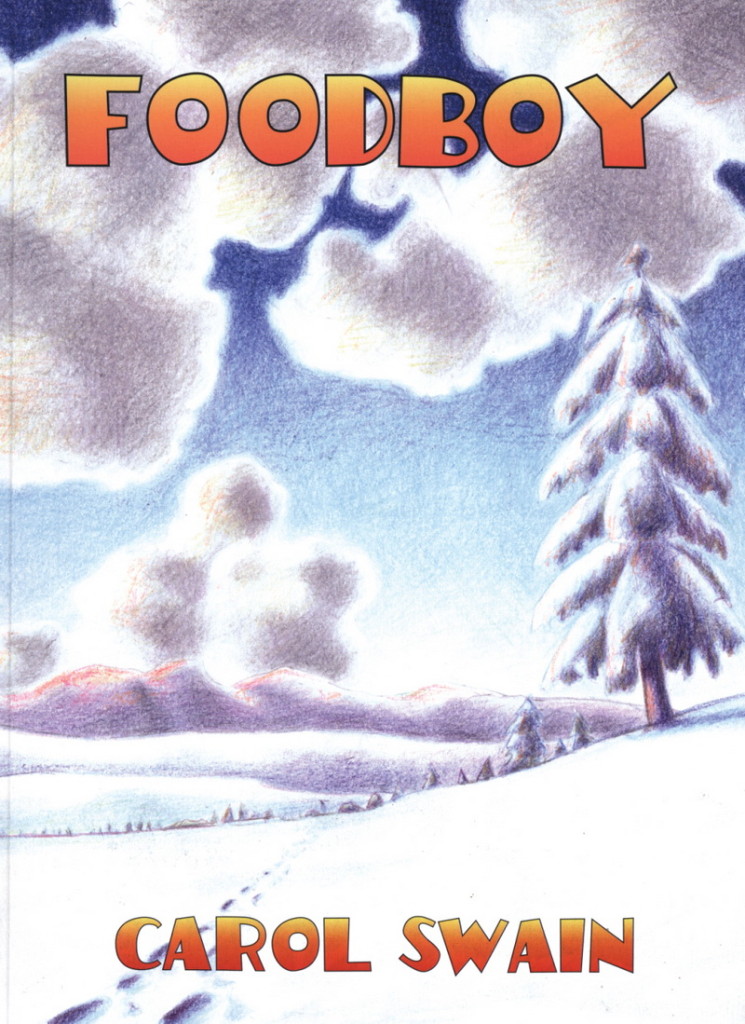

By the time of Foodboy the Welsh landscape that once yielded metallurgical wealth, now attracted the tourist coin. The youngsters are sardonic about it, but when Gareth finds a job, it’s in a hotel. Ross’ mother’s job is in a tourist shop, and the youngsters are fascinated and bemused by what people buy. Swain’s snow-scene cover perhaps channels this, but spot the subtly bleak detail: the footsteps disappearing into the snow. Ross accumulates in his den a collection of picture postcards and “souvenir s#!+”. Gareth calls this a shrine, but Ross, signalling his wry sophistication, clarifies that it’s a reliquary. The implication being that he is not a worshipper of these things, more an anthropologist.

If there is religion in these pages it’s Pantheism: the belief in a single divinity encompassing people and the landscape. Ross is trying to get back to this in the most complete way, eventually rejecting the hotel food Gareth brings him, in favour of a more paleolithic diet.

Swain’s artwork is in keeping with this, and unusually for comics, focusing on figures in landscape. The compositions are dazzling, at times bordering on abstract. The figures and faces have a monumental quality, as if themselves hewn out of that same landscape. All of this is rendered in her trademark pencil shades, looking here more nuanced than ever.

It was her short comics that made her name, but Swain effortlessly expands her themes into graphic novel form. She remains unique in the medium, and this is some of her best story and art, seamlessly integrated into a thoroughly original and powerful graphic novel.