Review by Frank Plowright

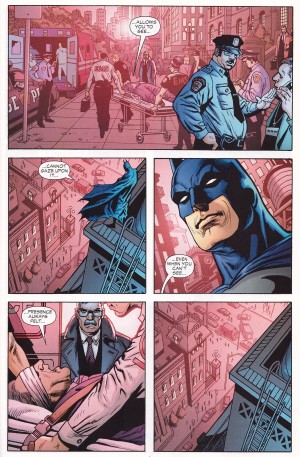

Many, many fine artists have illustrated a Batman strip, but it’s doubtful that any of them has equalled the seemingly effortless elegance provided by the combination of José Luis García-López pencilling and Kevin Nowlan supplying the inks. It’s a masterclass in refined storytelling. His Batman swoops and tumbles with a grace rarely seen, yet combined with a physical presence. This, however, isn’t the skulker in the shadows of night, but a gymnast and detective operating in broad daylight, which is novel in the 21st century.

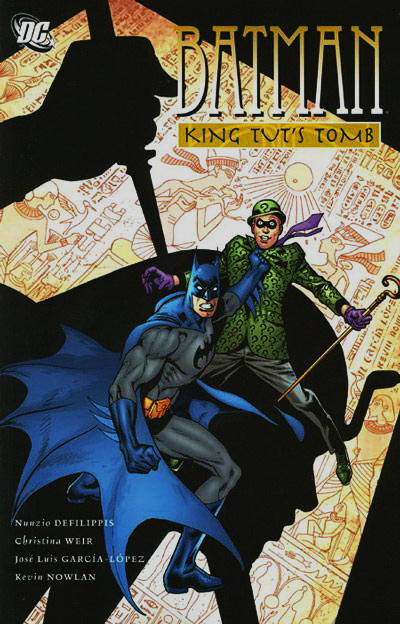

It would be nice to report that the strips matched the quality of the art, but that’s all too rarely been the case for García-López. The 2009 title feature runs to three chapters and toys with the idea of a villain from the 1960s Batman TV show who’d never featured in the comics, but this is a different King Tut. He’s not a portly buffoon, but a slim man dressed like an ancient Egyptian and mouthing riddles. And Batman knows someone whose expertise is riddles.

The involvement of the Riddler is narrative necessity. With a deductive plot, writers Nunzio DeFilippis and Christina Weir need someone to whom Batman explains his reasoning, but their version of the Riddler is an irritant, and surely no-one buys a Batman graphic novel to see the Riddler solving the clues. The plot twists well enough to a melodramatic conclusion, but it’s the art that’s the star of the only 21st century content.

A thematic link of museum exhibitions segues into J.M. DeMatteis’ teaming of Batman with Hawkman, an antiquities expert in his civilian identity. There’s an interesting twist, but much of the story passes with the heroes battling museum exhibits brought to life, and it’s only García-López’s superb adaptability with very different story elements that’s memorable.

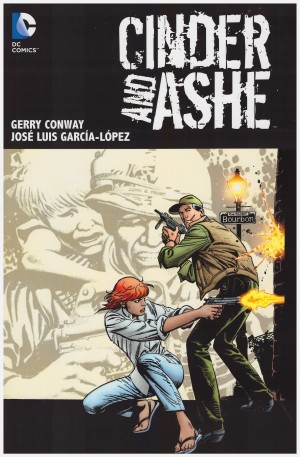

Overlooking the rather dubious convenience of sending Batman back to 1862 via hypnosis, Gerry Conway’s subsequent teaming of him with the native American Scalphunter – excuse the name – is neat. He transposes the abrasive and single-minded Florence Nightingale from the almost contemporary Crimean War to the American Civil War as Martha Jennings, and embeds a humanity at the core of the story. It’s the best in the book, although as with all this earlier material, the vivid colouring of the era doesn’t transfer well to the gloss stock used. It’s interesting to see the blue and the grey of Batman’s costume mixing with Civil War troops, though.

The pre-homicidal Joker of the late 1970s and early 1980s was only ever really characterised with distinction by Steve Englehart and Marshall Rogers in Strange Apparitions, and Conway’s plot for his appearance in a Batman issue of the era modifies Lex Luthor’s masterplan in the 1970s Superman film. Based on one of the early pages, García-López has looked at Rogers’ page layouts, but even his superb draughtsmanship can’t elevate a very ordinary encounter.

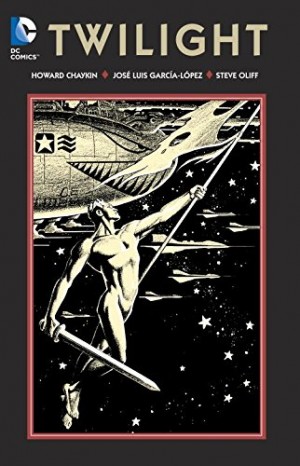

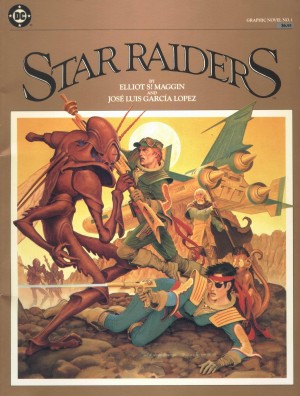

García-López spent the 1970s and 1980s illustrating DC material extremely unlikely to be reprinted any form other than bulky pulp collections, and thereafter his comics have been few and far between. It’s a treat therefore to have so much collected in a durable format, and with the current prices for used copies this deserves a place on your bookshelf for his art alone.