Review by Graham Johnstone

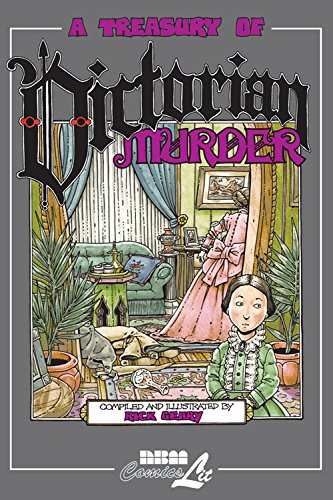

Rick Geary’s A Treasury of Victorian Murder, is a slim volume that spawned a whole series. The later volumes are book-length explorations of a single murder case. This first volume though, introduces the idea. While the sequels can be read in any order, it’s worth starting here.

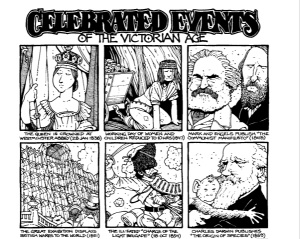

First of all it sets the scene of the Victorian era, named of course after the British Queen who ruled from 1837 to 1901. He shows us some of its ‘Celebrated Events’ (pictured): ranging from “the ill fated charge of the light brigade” when cavalrymen with sabres attacked an artillery battery, through to the publication of Sigmund Freud’s Interpretation of Dreams. An era, then of massive technological and social change.

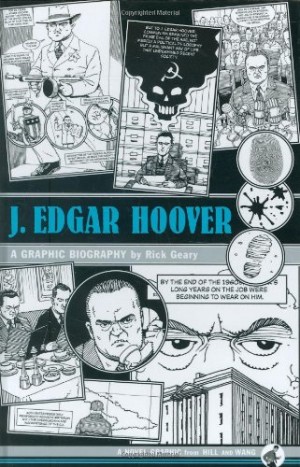

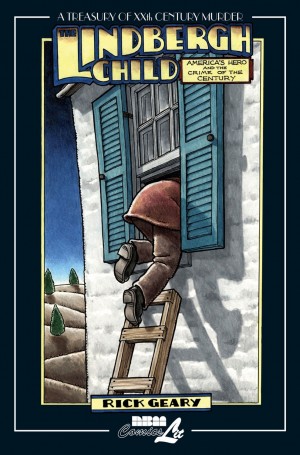

He also shows us some of the period’s key characters: statesman, explorers and innovators, those in literature and the arts as well as our focus here – ‘Murderers and Murderesses’. Geary is an understated caricaturist. He captures the likenesses of those we know, adding enough subtle exaggerations to make them instantly recognisable in these small panels. For those we don’t know, he intrigues us with visual hints at character, prompting, for example, speculation about their motivation to murder.

These mini portraits capture the look of early photographs. With the addition of title plates, and descriptions, they become like period cigarette cards. Presenting the murderers with deadpan captions alongside the politicians and creative people makes them seem just another strand of Victorian society.

After this there are short dramatisations of the murderous stories of Tim Ryan, Dr Pritchard, and Mary Pearcey, based respectively in America, Scotland and England.

‘The Ryan Mystery’ focusses on the death of two siblings in their tiny apartment. ‘Mary Pearcey’ on the brutal murder of a young mother and toddler. Both are a mere ten pages long – perhaps intended to be published in anthologies, or prepared as samples to pitch the series. ‘The Crimes of Dr E.W. Pritchard’ is the longest, at thirty pages, and so closer to the more detailed investigations of the later books.

Geary avoids sensationalism, and the murders happen off-stage. In the Pearcey story, the crime is shown mainly as an upturned pram. In another story we see bodies on the floor, and blood splattered around, but no gaping wounds. The conclusions are variously unsolved, or more or less certain. Even where the culprit is revealed, we’re still left to speculate about their motives.

They have a palpable ‘you are there’ quality: Geary puts us inside the case, not as murderer or victim, but as one of the investigation team. We see the various clues, the fragments of evidence, and have to piece it together.

Geary’s visual style is like a modern take on period engravings – inked in a mixture of contour hatching, restrained stippling, and spot blacks. On close scrutiny, this is visually closer to the extravagant whimsy of his early shorts, than the ‘just the facts’ simplicity of the later murder volumes. Geary typically borders on the cute, yet here it elegantly complements the darkness of the subject matter, and the always calm, sober tone of the narration.

He crams a lot into these small, intricately designed pages. He’s the master of little telling details, vividly shown: in the early shorts it was the peculiarities of modern America, but here it’s the clues and forensic details. We’re told a razor is missing from one crime scene, and shown its empty case: there’s a clear impression left in the soft lining, where the implement should be.

Whether you’re interested in Victorian times, or detection, or not, there’s plenty of wit and accomplished craft to enjoy here.